In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

Rashod Taylor: Little Black Boy

I want to start by asking you who you are, where you're from, and where you currently are?

I’m Rashod Taylor from Bloomington, Illinois, where I currently reside.

I took an interest in photography early on, looking at family albums — my mom and dad always took pictures of every single thing. I still have their old Vivitar 35 mm camera around here somewhere. In high school, I did photojournalism for the school newspaper and yearbook. I ended up doing photography in college, graduating with an art degree with an area of specialization in fine art photography.

After college, there were no jobs for a fresh-out-of-college student who’s an artist, so I went back home after school. I worked a bit as an assistant for a commercial photographer and at a portrait studio, but then I got into financial services. I've been there ever since, but I've been doing photography throughout, so I never stopped making images. It’s something I do outside of my 9 to 5.

I took an interest in photography early on, looking at family albums — my mom and dad always took pictures of every single thing. I still have their old Vivitar 35 mm camera around here somewhere. In high school, I did photojournalism for the school newspaper and yearbook. I ended up doing photography in college, graduating with an art degree with an area of specialization in fine art photography.

After college, there were no jobs for a fresh-out-of-college student who’s an artist, so I went back home after school. I worked a bit as an assistant for a commercial photographer and at a portrait studio, but then I got into financial services. I've been there ever since, but I've been doing photography throughout, so I never stopped making images. It’s something I do outside of my 9 to 5.

It's incredible to see you producing this amazing work while knowing you also have many other things going on. Can you talk a about the project you've been working on, photographing your son? When did it start, and what your intention behind it is?

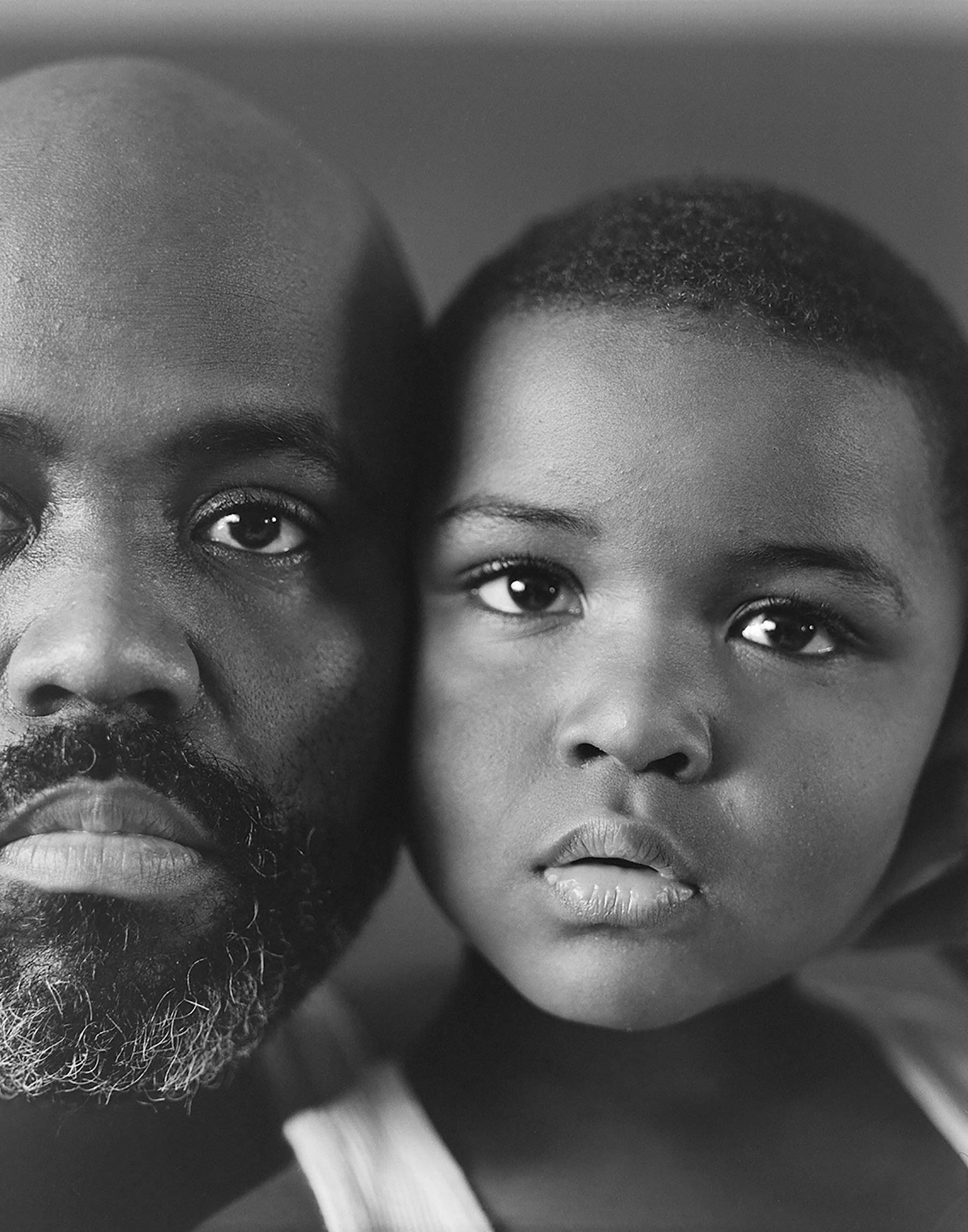

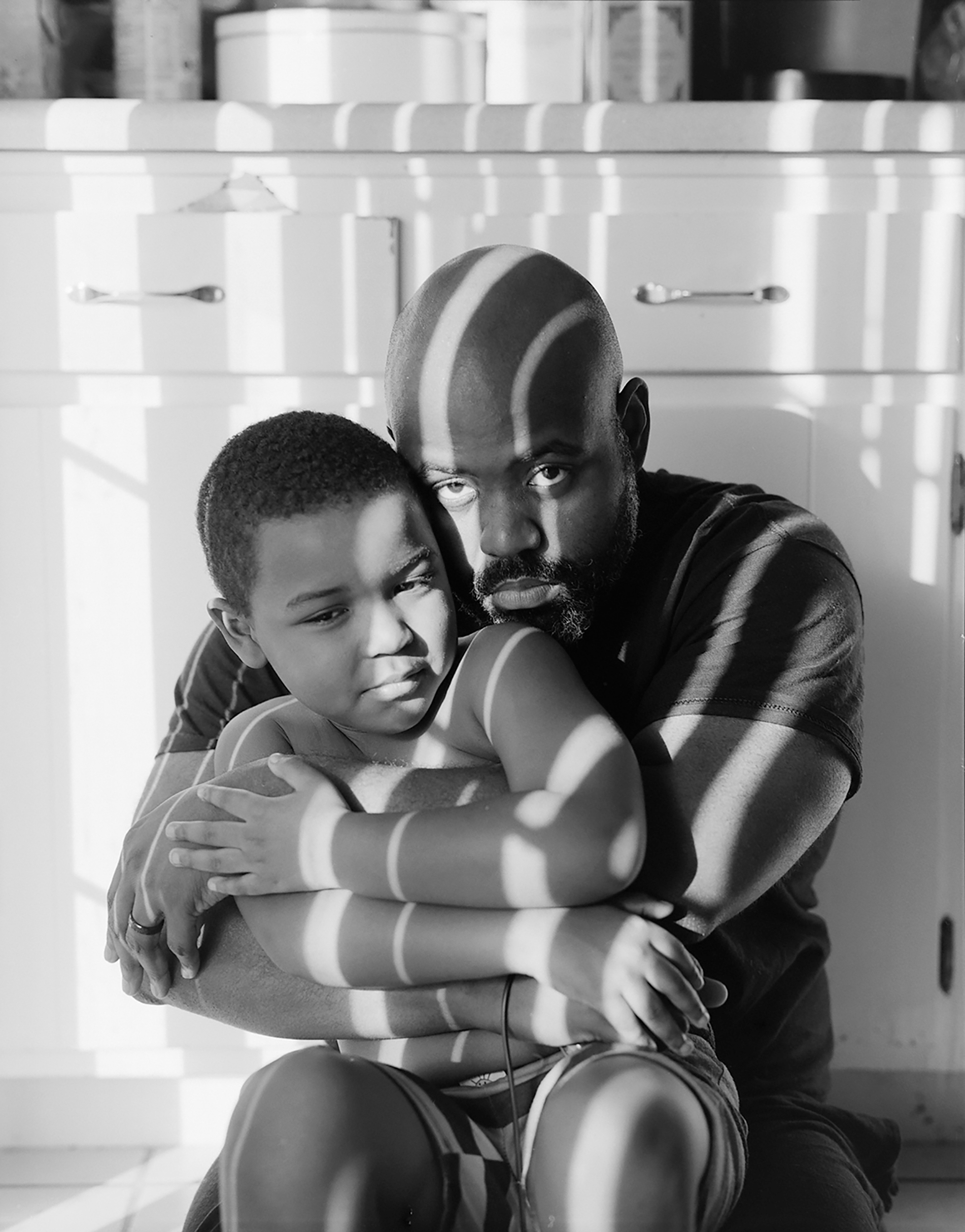

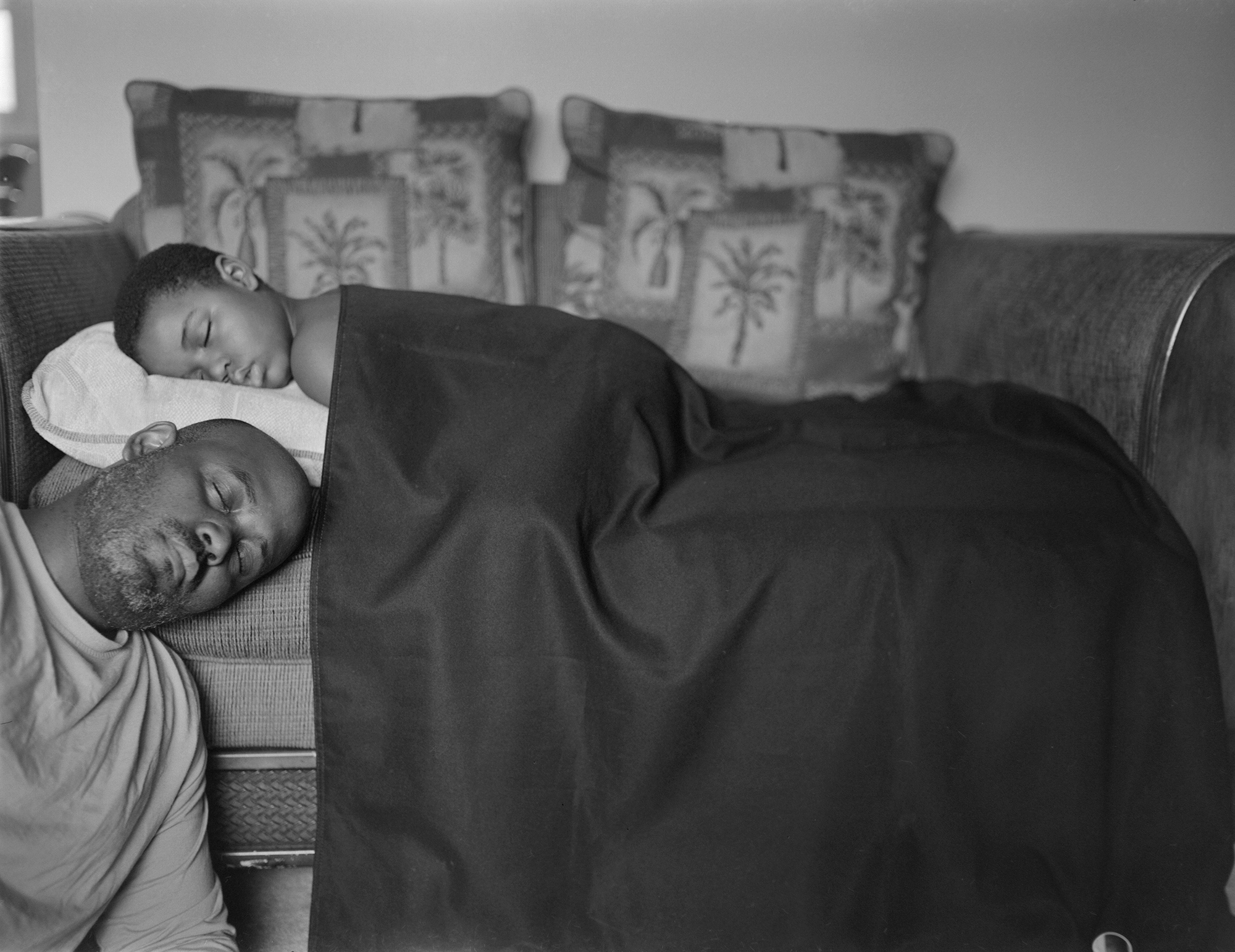

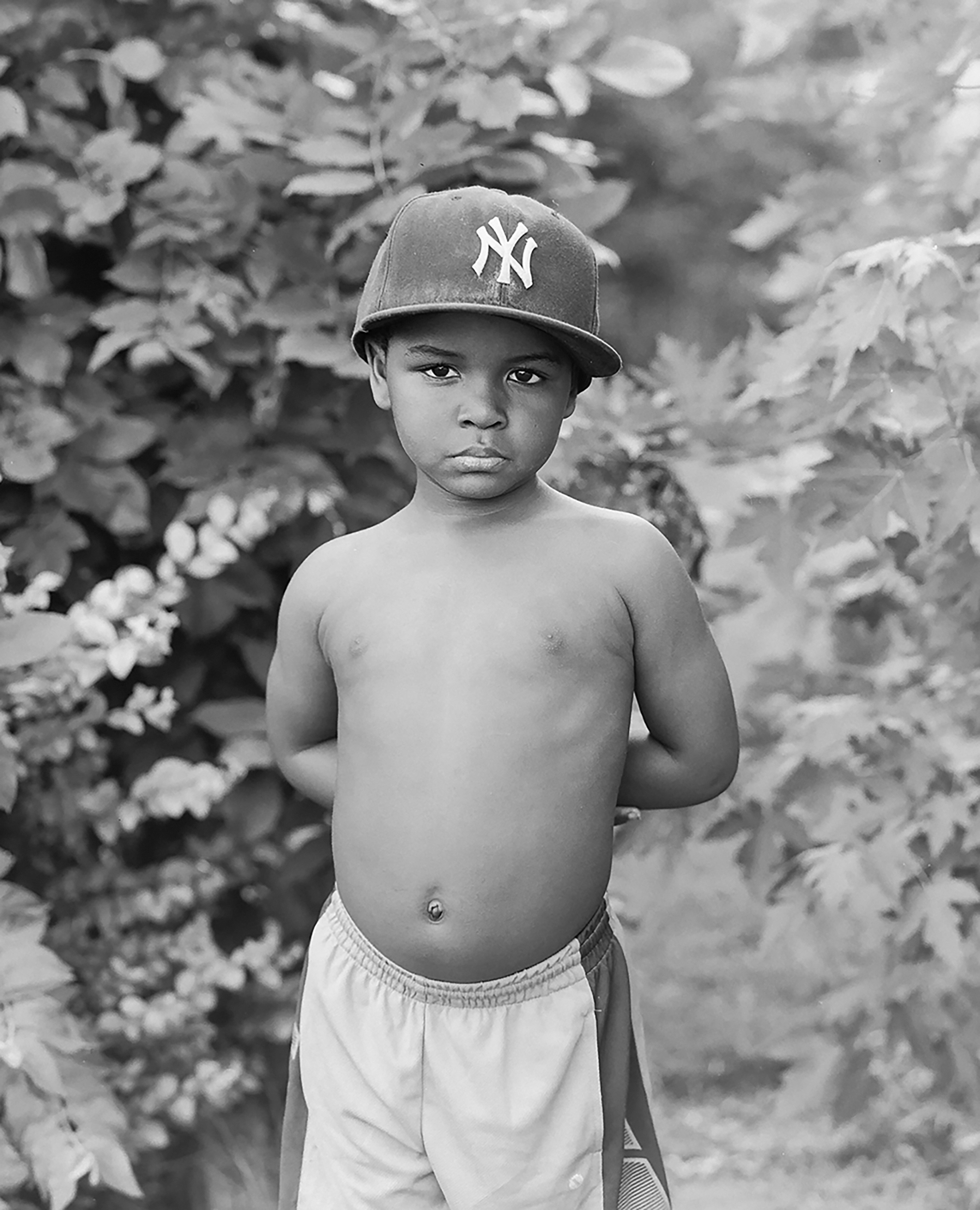

It started with being a first-time father. LJ, my son, is five. I began making photographs when he was born, with a 35 mm camera — the standard dad photos. You take pictures of everything your kids do, essentially. I started to look through all those images, and it dawned on me. There's many things in the photographs — whether it’s the way he's juxtaposed against another kid or what he's wearing or what he's doing — there's nothing in there that you wouldn't see a kid do. But I saw this thread that I wanted to show what it is to be a little Black boy because, on the surface, it's a lot of the same things any kid would do; however, he sees things a different way than other kids. I have to help him learn how to navigate life — in general and as a Black and Dominican boy. As a person of color and what that looks like in this world.

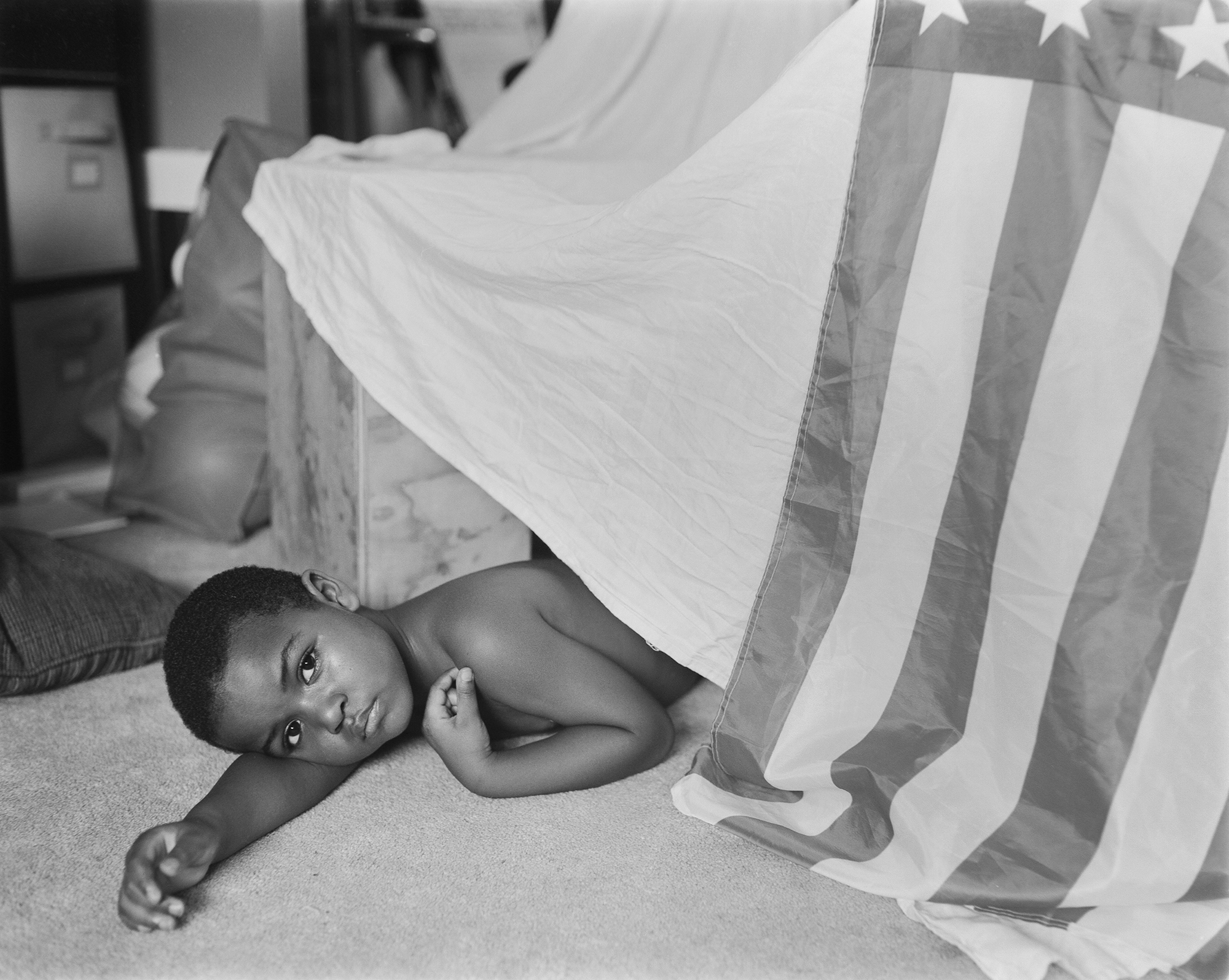

I started adding different elements in the images that go along with that journey. It's called Little Black Boy. It's about him, but at the same time, I'm dealing with my insecurities and vulnerabilities as it pertains to raising him. That comes through in some of the imagery. It's this real investigation of his childhood growing up Black in America, and me navigating fatherhood and parenthood, and, in a way, feeding off each other.

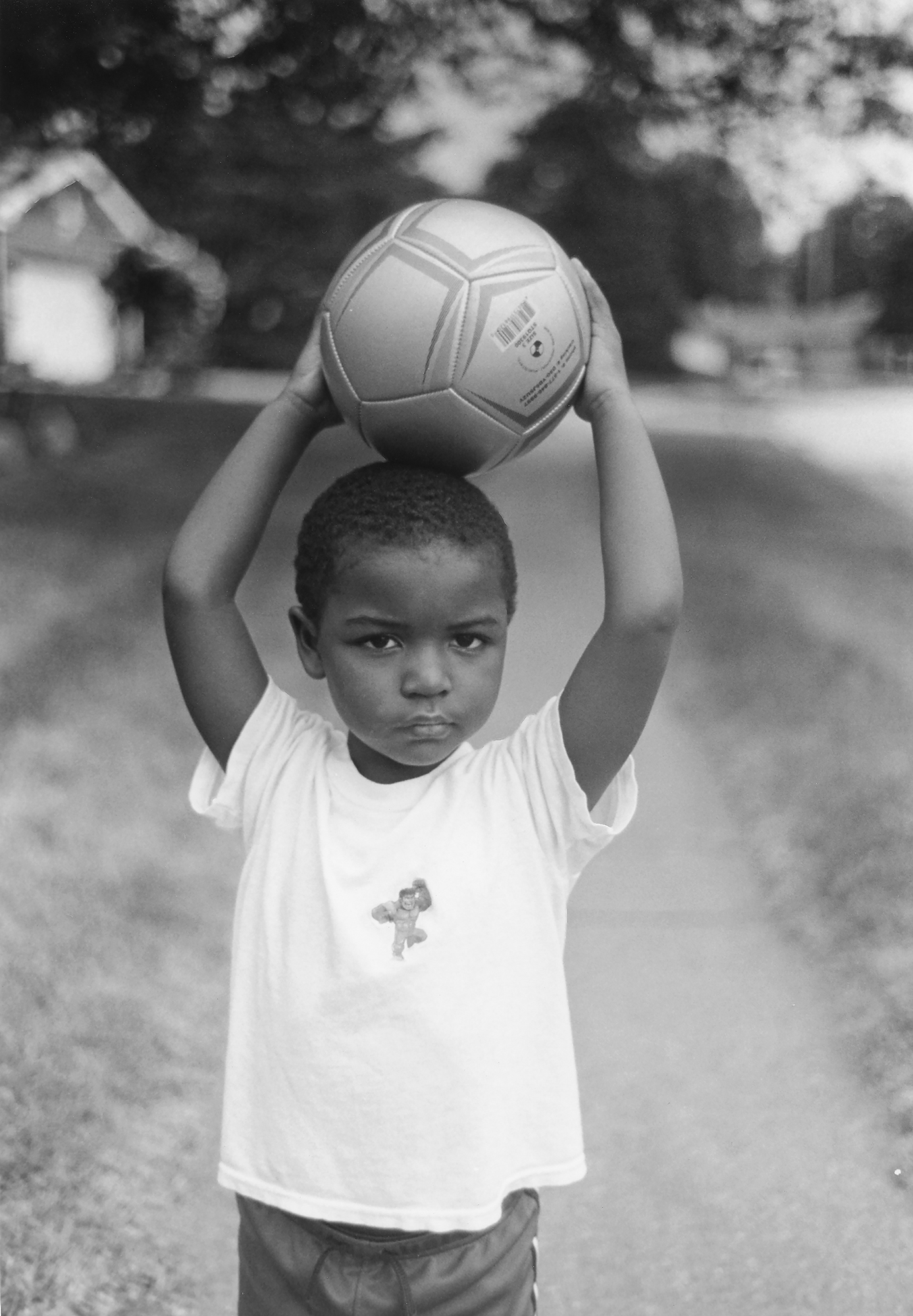

Every image is not necessarily an image where there's this super-deep underlying meaning, but then there's a lot of pictures that are. Some of the photos are light and reminiscence of childhood. I like that dynamic. I try to do a little bit of both and mix it up a little bit.

I started adding different elements in the images that go along with that journey. It's called Little Black Boy. It's about him, but at the same time, I'm dealing with my insecurities and vulnerabilities as it pertains to raising him. That comes through in some of the imagery. It's this real investigation of his childhood growing up Black in America, and me navigating fatherhood and parenthood, and, in a way, feeding off each other.

Every image is not necessarily an image where there's this super-deep underlying meaning, but then there's a lot of pictures that are. Some of the photos are light and reminiscence of childhood. I like that dynamic. I try to do a little bit of both and mix it up a little bit.

I was going to ask about the process you have in terms of the type of camera you use — and how did you keep your son still?

4x5 large format camera, some black and white film. It helps slow me down and take my time, compose an image, look at the light, and put something that I like together in the ground glass. It helps with LJ, too. Early on, it was more challenging because he was three, three-and-a-half. Most of the images on my site, he's probably four in all of these. There are some earlier images that I shot more with a medium format. That's a little easier, he's still four in some of these, so it's a matter of knowing what I want and getting him to do it. "Hey, sit right here, and read this book," or "Sit down for a minute." I get myself together and try to talk to him to keep him occupied.

At this point, he knows that we're going to take a photograph, and he does well at sitting and knowing — he's like, "Okay, Daddy, I'm ready for the picture. Go get your big camera.” I’ve got him pretty well-conditioned at this point. It was a lot more challenging at first, but now he's gotten into his own groove — he’s a good little actor.

At this point, he knows that we're going to take a photograph, and he does well at sitting and knowing — he's like, "Okay, Daddy, I'm ready for the picture. Go get your big camera.” I’ve got him pretty well-conditioned at this point. It was a lot more challenging at first, but now he's gotten into his own groove — he’s a good little actor.

Your work is so powerful. It's personal, and it's your son, but I see my own family when I look at these pictures. That's why I love the work so much. I see such tenderness and fragility. Did you see images like that of people who looked like you when you were growing up? Where did this vision come from?

We see some things in terms of Black life when looking at Gordon Parks and others, but honestly, there's not really any imagery depicting that. One of my influences and inspirations is Sally Mann. I enjoy her work, but then you think, "Well, I don't see any people of color making work like that."

I try to keep things simple — I want to focus on the everyday. I feel like that's where I make the best art, when I focus on the things I love and am passionate about. Photographing everyday life is heightened because it's a Black man photographing his son, which happens, but it's not mainstream in society. A lot of it has to do with people not having any exposure to it. When people interact with the work, it's like, "Wow, this is touching." You don't often see those types of images. It’s more of the opposite — you see the negative connotations and negative stereotypes of the Black family in general, of Black males and Black women. It was important to show the truth.

That truth has always been there. You know that, I know that. It's not like when you’re Black, you do different things growing up as a kid — we go on vacations. We play outside. We have friends. We go to our grandparents' house. We wear our parents' clothes. We do all of those things, but in society, no one takes the time to see who you are, that we're here and that we matter. All that's in the work, with some of my fears sprinkled in that go with his life and what I'm feeling.

I try to keep things simple — I want to focus on the everyday. I feel like that's where I make the best art, when I focus on the things I love and am passionate about. Photographing everyday life is heightened because it's a Black man photographing his son, which happens, but it's not mainstream in society. A lot of it has to do with people not having any exposure to it. When people interact with the work, it's like, "Wow, this is touching." You don't often see those types of images. It’s more of the opposite — you see the negative connotations and negative stereotypes of the Black family in general, of Black males and Black women. It was important to show the truth.

That truth has always been there. You know that, I know that. It's not like when you’re Black, you do different things growing up as a kid — we go on vacations. We play outside. We have friends. We go to our grandparents' house. We wear our parents' clothes. We do all of those things, but in society, no one takes the time to see who you are, that we're here and that we matter. All that's in the work, with some of my fears sprinkled in that go with his life and what I'm feeling.

It's a powerful act, to document your family and share it. It’s going to impact the way people see what family looks like, what childhood looks like, what Black parenting looks like. I wonder how different it would be if it was someone outside of your community or someone coming in from the outside and photographing your family? How different those pictures would be versus you creating the work yourself?

That's an interesting thought. I think you're 100% right, it would be very different. Different photographers have a way of making great images with people they meet, right? However, I think there's this intimacy and presence when dealing with the people you truly love and who are part of your family. It takes the images to the next level because I care and love them so deeply that — I hope — that comes through with the images. I think about him and I try to help him navigate this life and show that through the series.

Is documenting your son something that you're continuing to do?

Yes. It's an ongoing project. I will be working on it for a while, at least another five to seven years. I want to capture him as he's going through childhood. I'm sure at a certain point, he may not want anything to do with me — that's fine, I'll stop, but up until that point, I'm going to keep shooting. For this project, I'm looking to have a book in as he gets to that past-childhood phase and early adolescence — definitely by his teenage years.. It will have a different meaning at that point. It won't have the innocence that I'm interested in, but I'm excited because I hope to turn it into more once it's a finished piece of work.

I wanted to ask you how does being a Black artist inform your work?

I will say this — it's a huge part of my photography per se, but I like the fact that other Black photographers may not have that as a part of their practice and are interested in other things. I think, sometime we get typecast: "Oh, he's a Black photographer or she's a Black photographer, so they have to photograph the struggle or racism," and those might be only the jobs they get or that's how people see them.

I believe that we can do anything we want to do, but it does include this work for me. It's the life I live every day, so it's honest and it's truthful — whether I like it or not, it comes out. Specifically, in this series, that plays a huge role in my son’s upbringing, and obviously a huge role in me being a father, a parent, a husband living in America.

I've come to a point where I've embraced it. It's one of those things where you get in those conversations with people and they act like you’re the spokesperson, and you’re not — I'm not speaking for all Black people. I'm not speaking for all Dominicans. At the same time, it is this way that we — people of color — are representative of the larger group, and since we haven't had that voice in so long, and it's been downtrodden and overlooked, I feel responsible for making sure that since this work has to do with that. I want to have it amplified as much as possible because many people can identify with it. It has that way of connecting with people, and I think that is good in terms of continuing these conversations on racism and injustice.

I believe that we can do anything we want to do, but it does include this work for me. It's the life I live every day, so it's honest and it's truthful — whether I like it or not, it comes out. Specifically, in this series, that plays a huge role in my son’s upbringing, and obviously a huge role in me being a father, a parent, a husband living in America.

I've come to a point where I've embraced it. It's one of those things where you get in those conversations with people and they act like you’re the spokesperson, and you’re not — I'm not speaking for all Black people. I'm not speaking for all Dominicans. At the same time, it is this way that we — people of color — are representative of the larger group, and since we haven't had that voice in so long, and it's been downtrodden and overlooked, I feel responsible for making sure that since this work has to do with that. I want to have it amplified as much as possible because many people can identify with it. It has that way of connecting with people, and I think that is good in terms of continuing these conversations on racism and injustice.

I want to advocate for artists of color, I'm sick and tired of them only getting assigned certain things, whereas white counterparts get the benefit of the doubt to shoot anything or any race. Why is that? I find such inspiration when I meet with artists like you who are doing artwork in a way that is so true to their lived experience. Your work is inspiring a lot of people. I hope you know that. I get emotional looking through all of your photography.

Thank you. I appreciate that. You got me. I was speaking at a conference, and I definitely was emotional — the tears were coming out of me. It was recorded, too. I'm like, "Oh gosh. Let me get through this before crying."