In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

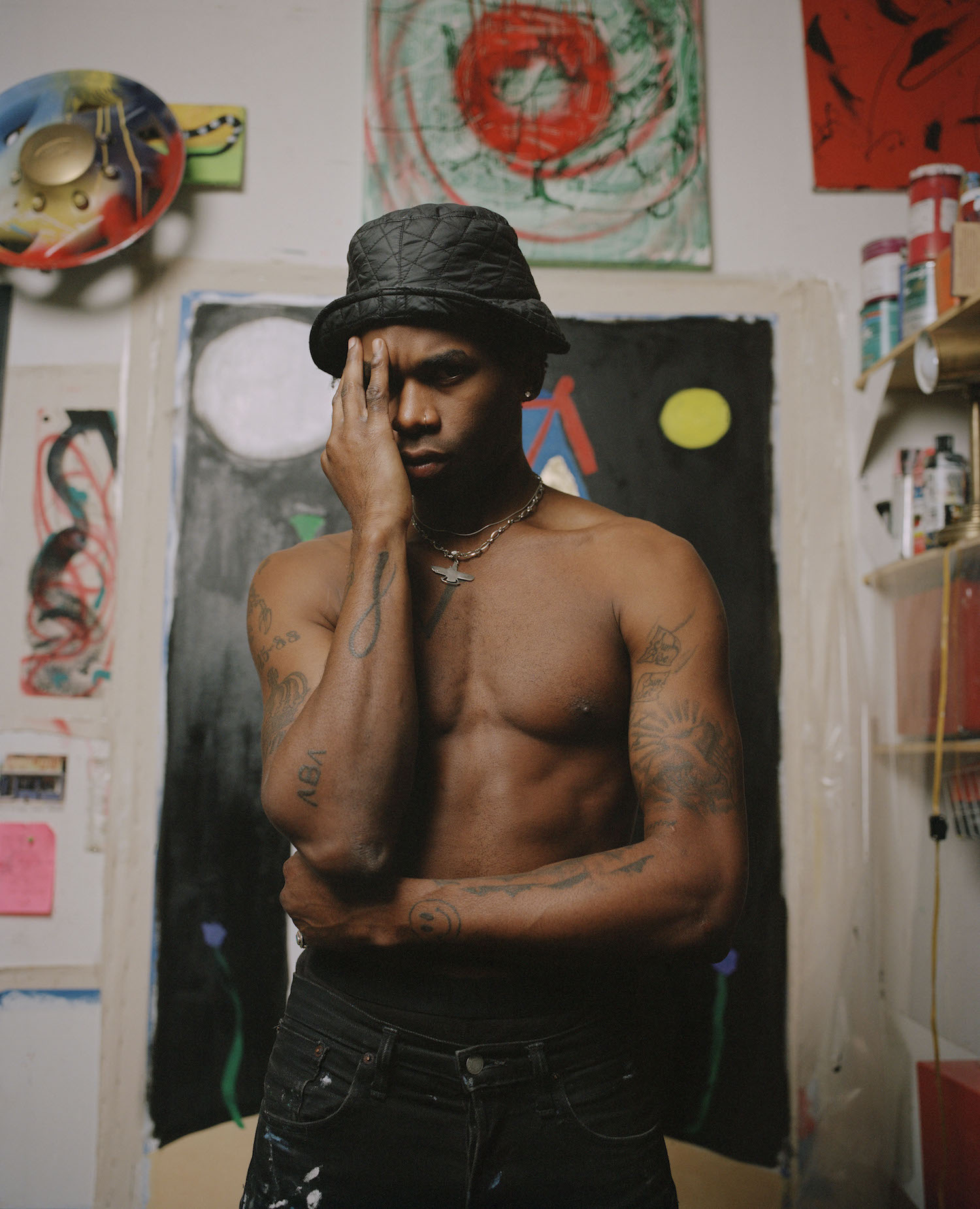

Nate Langston Palmer:

Portfolio Overview

I can’t recall how I first came across your work, but as soon as I saw it, I was so moved by the images, and the way you documented people. Can you share some context? Where are you from and where are you taking images now?

It's funny to me when people tell me that they really like my work, that they see something in it, because it forces me to look up for a minute, which is really nice. I appreciate it. I'm born and raised in Washington DC. I started photography – I think I was about 12 or 13 when I got my first camera. It was a little point-and-shoot digital camera that I would take around. I would carry it in my pocket all the time, take pictures with friends and all that kind of stuff. We were lucky to have a dark room in the high school that I went to. I was also really fortunate to have a great photo teacher who really believed in me. He's a Black man. It was a really powerful relationship, and it definitely helped me grow.

I certainly did not understand how powerful that was at the time, but he gave me a lot of guidance and he's been there since day one and he's still a part of my life. We still talk often and catch up. I actually photographed him a few times last year. There's a few of those photos on my Instagram. I got straight into film photography on 35-millimeter black and white. From there, I picked up and after high school, I went to Tisch at NYU.

I certainly did not understand how powerful that was at the time, but he gave me a lot of guidance and he's been there since day one and he's still a part of my life. We still talk often and catch up. I actually photographed him a few times last year. There's a few of those photos on my Instagram. I got straight into film photography on 35-millimeter black and white. From there, I picked up and after high school, I went to Tisch at NYU.

No, way. I was at Gallatin. It's amazing hearing your journey because I had a photo teacher in high school that completely shaped the course of my life -- I spent most of my time in high school in the dark room and it sparked my love for photography.

Nice. I graduated, I spent almost two and a half years in Australia and Sydney just living and working .And then two years ago, I moved back to DC and I've been full-time freelance ever since, spending as much of my free time as I can working on personal projects. It's been therapeutic to be back in DC and to be photographing where I came from and the streets and the neighborhoods that are really familiar to me, where I know people and that sort of thing.

Being from DC, what does DC mean to you? How do you feel DC plays a role in your art and what does it mean to you to be photographing where you're from?

I think that changes all the time because I've discovered so much more about the city in the past few years. The city is changing constantly. When I moved back here, I'd been away for six or seven years, and DC is one of the most gentrified cities in the country. In that time period when I was gone, my neighborhood where I grew up - it was just hit by that wave of gentrification. This area has changed dramatically. There are lots of people who used to be in the area, predominantly Black people, who have either been pushed out, or sold their homes, or moved out for other reasons, or just left the community because it doesn't feel like theirs anymore. It's hard to watch because it feels more and more unfamiliar the more time passes. It's been really nice to engage with the people in my city more and I see photography as that tool to engage with the community that I had grown up in, but not fully explored before.

Part of the reason I’m compelled is quietness in the images. All that movement you're talking about in those changes, I feel like in the photographs, there's this stillness that urges the viewer to pause and reflect and it gives reverence to a community.

It's nice to hear that because it's what I'm trying to find when I am interacting with someone through the camera. I look for those moments that are really still and really quiet and either give room to reflect or show somebody who might be reflecting on something. I was really excited that you asked me to be part of the Embracing Stillness exhibition because that is something that I think, as a society, we do not pay nearly enough attention to – finding that stillness and how important that is, because the amount of chaos that is going on on this planet right now is really, really insane.

I find it so interesting that in the midst of being in a city that is undergoing massive transformation you’re seeking out less dramatic moments within the tumultuous time. There's so many ways to approach the topic of displacement and gentrification. Do you feel like that's a conscientious choice that you're focusing on the Black experience?

It definitely is. On one hand, I do photograph what I'm attracted to, like I think all photographers do or should do. I am drawn to, in a more organic sense, photographing the Black community in DC. That being said, it also is a conscientious decision to photograph Black people and to show them in a light that they're not always seen in.

I think it's something that has been done over and over again. It's been done more and more frequently, but it still is important. Representation is still really important, and being able to tell our own stories and be represented in a way that we feel brings us dignity and to be able to honor the people who I take pictures of is really important to me.

I think it's something that has been done over and over again. It's been done more and more frequently, but it still is important. Representation is still really important, and being able to tell our own stories and be represented in a way that we feel brings us dignity and to be able to honor the people who I take pictures of is really important to me.

That is exactly why I founded LISTO, because it really matters and I don't think there's ever enough of it. There's so much time to make up for. We’ve got to keep it coming. The dignity part, you mentioned. There's such a level of dignity and an honoring of people that you're photographing. It does not feel exploitative. It is really thoughtful, and that's what I want to see more of.

You and me both.

Not just passing through a city for fun. There's a connection in all your images that's happening.

I have a really hard time processing the genre of photojournalism, because I don't really know where to box myself in. That's not a bad thing, unless you're writing a bio and then I don't know where to put myself. I think there is a lot of work to be done in the photojournalism industry as a whole -- I don't consider myself -- I do not have the right, even as a Black man, to go into a Black community and take photographs from them. That goes for any photographer no matter what background you come from.

The pace in which they expect you to get images and turn them around. That's where I think it can cross a line, where it becomes unethical. Because that room to spend time with the people you're photographing, and to make sure that you're representing them in a way that they want to be represented, that takes time. It is not something that happens overnight.

The pace in which they expect you to get images and turn them around. That's where I think it can cross a line, where it becomes unethical. Because that room to spend time with the people you're photographing, and to make sure that you're representing them in a way that they want to be represented, that takes time. It is not something that happens overnight.

It's important for people to understand that even as diverse artists. We're not just automatically boom, walking into space, and then now we have the authority because of our skin color to quickly document people and make money off of those images. Documentary and photojournalism have a complicated history and I can imagine it can be challenging to put yourself in that category of imagery.

Exactly.

I would love for all of us to really rethink what photojournalism is and how we get consent from the people we photograph and these deadlines.

One of the things about that is, that I've been thinking about is, all due respect to editors, but editors are sitting in an office in New York City, sitting in an office in DC. If you're going into a community, you're sending a photographer into the community, they are the ones who are being held responsible by the people that they're photographing to represent them in a way that they feel is appropriate.

I think a big part of that also the job is to educate photographers who are just coming into the industry. Because even myself in the past two years, I've learned a lot about how stuff works and what kind of information editors should be passing along, and what sort of situation they should be putting you in and not putting you in. I didn't know any of that. I was taking whatever job came to me. I was just stoked that anybody even wanted me to photograph them, but you don't realize that you do have authority. You should be able to feel comfortable asking questions and knowing what you deserve going into certain situations.

I think a big part of that also the job is to educate photographers who are just coming into the industry. Because even myself in the past two years, I've learned a lot about how stuff works and what kind of information editors should be passing along, and what sort of situation they should be putting you in and not putting you in. I didn't know any of that. I was taking whatever job came to me. I was just stoked that anybody even wanted me to photograph them, but you don't realize that you do have authority. You should be able to feel comfortable asking questions and knowing what you deserve going into certain situations.