In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

Nate Langston Palmer:

Portfolio Overview

I can’t recall how I first came across your work, but as soon as I saw it, I was so moved by the images, and the way you documented people. Can you share some context? Where are you from and where are you taking images now?

It's funny to me when people tell me that they really like my work, that they see something in it, because it forces me to look up for a minute, which is really nice. I appreciate it. I'm born and raised in Washington DC. I started photography – I think I was about 12 or 13 when I got my first camera. It was a little point-and-shoot digital camera that I would take around. I would carry it in my pocket all the time, take pictures with friends and all that kind of stuff. We were lucky to have a dark room in the high school that I went to. I was also really fortunate to have a great photo teacher who really believed in me. He's a Black man. It was a really powerful relationship, and it definitely helped me grow.

I certainly did not understand how powerful that was at the time, but he gave me a lot of guidance and he's been there since day one and he's still a part of my life. We still talk often and catch up. I actually photographed him a few times last year. There's a few of those photos on my Instagram. I got straight into film photography on 35-millimeter black and white. From there, I picked up and after high school, I went to Tisch at NYU.

I certainly did not understand how powerful that was at the time, but he gave me a lot of guidance and he's been there since day one and he's still a part of my life. We still talk often and catch up. I actually photographed him a few times last year. There's a few of those photos on my Instagram. I got straight into film photography on 35-millimeter black and white. From there, I picked up and after high school, I went to Tisch at NYU.

No, way. I was at Gallatin. It's amazing hearing your journey because I had a photo teacher in high school that completely shaped the course of my life -- I spent most of my time in high school in the dark room and it sparked my love for photography.

Nice. I graduated, I spent almost two and a half years in Australia and Sydney just living and working .And then two years ago, I moved back to DC and I've been full-time freelance ever since, spending as much of my free time as I can working on personal projects. It's been therapeutic to be back in DC and to be photographing where I came from and the streets and the neighborhoods that are really familiar to me, where I know people and that sort of thing.

Being from DC, what does DC mean to you? How do you feel DC plays a role in your art and what does it mean to you to be photographing where you're from?

I think that changes all the time because I've discovered so much more about the city in the past few years. The city is changing constantly. When I moved back here, I'd been away for six or seven years, and DC is one of the most gentrified cities in the country. In that time period when I was gone, my neighborhood where I grew up - it was just hit by that wave of gentrification. This area has changed dramatically. There are lots of people who used to be in the area, predominantly Black people, who have either been pushed out, or sold their homes, or moved out for other reasons, or just left the community because it doesn't feel like theirs anymore. It's hard to watch because it feels more and more unfamiliar the more time passes. It's been really nice to engage with the people in my city more and I see photography as that tool to engage with the community that I had grown up in, but not fully explored before.

Part of the reason I’m compelled is quietness in the images. All that movement you're talking about in those changes, I feel like in the photographs, there's this stillness that urges the viewer to pause and reflect and it gives reverence to a community.

It's nice to hear that because it's what I'm trying to find when I am interacting with someone through the camera. I look for those moments that are really still and really quiet and either give room to reflect or show somebody who might be reflecting on something. I was really excited that you asked me to be part of the Embracing Stillness exhibition because that is something that I think, as a society, we do not pay nearly enough attention to – finding that stillness and how important that is, because the amount of chaos that is going on on this planet right now is really, really insane.

I find it so interesting that in the midst of being in a city that is undergoing massive transformation you’re seeking out less dramatic moments within the tumultuous time. There's so many ways to approach the topic of displacement and gentrification. Do you feel like that's a conscientious choice that you're focusing on the Black experience?

It definitely is. On one hand, I do photograph what I'm attracted to, like I think all photographers do or should do. I am drawn to, in a more organic sense, photographing the Black community in DC. That being said, it also is a conscientious decision to photograph Black people and to show them in a light that they're not always seen in.

I think it's something that has been done over and over again. It's been done more and more frequently, but it still is important. Representation is still really important, and being able to tell our own stories and be represented in a way that we feel brings us dignity and to be able to honor the people who I take pictures of is really important to me.

I think it's something that has been done over and over again. It's been done more and more frequently, but it still is important. Representation is still really important, and being able to tell our own stories and be represented in a way that we feel brings us dignity and to be able to honor the people who I take pictures of is really important to me.

That is exactly why I founded LISTO, because it really matters and I don't think there's ever enough of it. There's so much time to make up for. We’ve got to keep it coming. The dignity part, you mentioned. There's such a level of dignity and an honoring of people that you're photographing. It does not feel exploitative. It is really thoughtful, and that's what I want to see more of.

You and me both.

Not just passing through a city for fun. There's a connection in all your images that's happening.

I have a really hard time processing the genre of photojournalism, because I don't really know where to box myself in. That's not a bad thing, unless you're writing a bio and then I don't know where to put myself. I think there is a lot of work to be done in the photojournalism industry as a whole -- I don't consider myself -- I do not have the right, even as a Black man, to go into a Black community and take photographs from them. That goes for any photographer no matter what background you come from.

The pace in which they expect you to get images and turn them around. That's where I think it can cross a line, where it becomes unethical. Because that room to spend time with the people you're photographing, and to make sure that you're representing them in a way that they want to be represented, that takes time. It is not something that happens overnight.

The pace in which they expect you to get images and turn them around. That's where I think it can cross a line, where it becomes unethical. Because that room to spend time with the people you're photographing, and to make sure that you're representing them in a way that they want to be represented, that takes time. It is not something that happens overnight.

It's important for people to understand that even as diverse artists. We're not just automatically boom, walking into space, and then now we have the authority because of our skin color to quickly document people and make money off of those images. Documentary and photojournalism have a complicated history and I can imagine it can be challenging to put yourself in that category of imagery.

Exactly.

I would love for all of us to really rethink what photojournalism is and how we get consent from the people we photograph and these deadlines.

One of the things about that is, that I've been thinking about is, all due respect to editors, but editors are sitting in an office in New York City, sitting in an office in DC. If you're going into a community, you're sending a photographer into the community, they are the ones who are being held responsible by the people that they're photographing to represent them in a way that they feel is appropriate.

I think a big part of that also the job is to educate photographers who are just coming into the industry. Because even myself in the past two years, I've learned a lot about how stuff works and what kind of information editors should be passing along, and what sort of situation they should be putting you in and not putting you in. I didn't know any of that. I was taking whatever job came to me. I was just stoked that anybody even wanted me to photograph them, but you don't realize that you do have authority. You should be able to feel comfortable asking questions and knowing what you deserve going into certain situations.

I think a big part of that also the job is to educate photographers who are just coming into the industry. Because even myself in the past two years, I've learned a lot about how stuff works and what kind of information editors should be passing along, and what sort of situation they should be putting you in and not putting you in. I didn't know any of that. I was taking whatever job came to me. I was just stoked that anybody even wanted me to photograph them, but you don't realize that you do have authority. You should be able to feel comfortable asking questions and knowing what you deserve going into certain situations.

In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

Ysa Perez: Portfolio Overview

My first question is where are you from? And where are you currently situated?

I was born in Puerto Rico and I moved to Rochester, New York, with my mom when I was four. I was raised in Rochester, but at the moment, I'm in Bushwick, New York.

I know you’re there now but I also have a sense that you’ve led a nomadic life of sorts. What has that been like for you for the past nine years? Where have you been? Where do you frequently travel to?

Well, it's been exciting, but also a blur. The blur only came with the pause with COVID. Only in the last six, seven months, I've been in an existential crisis of, "What have I been doing? What am I chasing? Do I feel the happiest when I'm constantly on the move or do I want stability? Do I want this?"

My first internship was at Nylon, which was cool. I still learned a lot because their interns did everything — they really worked.

When I got to GQ, my boss was photo director Dora Somosi — she was my hero. I was blown away. I learned so much — how photo editors discuss work, how they assign work. It felt really exciting to be a part of those meetings, even though I never said anything.

My first internship was at Nylon, which was cool. I still learned a lot because their interns did everything — they really worked.

When I got to GQ, my boss was photo director Dora Somosi — she was my hero. I was blown away. I learned so much — how photo editors discuss work, how they assign work. It felt really exciting to be a part of those meetings, even though I never said anything.

You’ve said you always knew you wanted to be a photographer. I wondered if you could talk about how that knowledge came to be, and coming from a Puerto Rican family, where you saw photography, or were introduced to it?

It came late in life. To be fair, my mom was and is very artistic. That's why we moved to Rochester, so she could go to the Rochester Institute of Technology — where, ironically, I went to school for photography. She went for graphic design. I grew up with my mom going to craft art shows.

I always remember tangible photographs, and I love those. Now, looking back on them, I realize, “Oh, my mom had an artistic eye, maybe it was somehow in there." All my basis for art was my mom. Up until last year, I never met my biological dad. My stepdad passed away five years ago.

I went to the University of Buffalo for a year and was taking basic foundation classes. I had a boyfriend at the time who went to RIT. This was during the MySpace days, and these two girls from RIT’s advertising photography program contacted me. They have a yearly project where they have to do a simulated campaign shoot. Because Rochester isn’t in New York City, RIT students always struggle to find models.

There was a weird “aha!” moment when I was in the studio with them and saw all this equipment — the facilities blew my mind. I was like, "What major is this?" They told me they were photography majors, and I knew immediately, "I'm going to go for that."

My first day of school was setting up a four-by-five camera. As a transfer student, they gave me no direction. I got a packet that said, "You go to RIT now." I showed up. The kids who went there, they took photography at specialized high schools before and were a little pretentious. Most of them don't do photography now. It's ironic.

I always remember tangible photographs, and I love those. Now, looking back on them, I realize, “Oh, my mom had an artistic eye, maybe it was somehow in there." All my basis for art was my mom. Up until last year, I never met my biological dad. My stepdad passed away five years ago.

I went to the University of Buffalo for a year and was taking basic foundation classes. I had a boyfriend at the time who went to RIT. This was during the MySpace days, and these two girls from RIT’s advertising photography program contacted me. They have a yearly project where they have to do a simulated campaign shoot. Because Rochester isn’t in New York City, RIT students always struggle to find models.

There was a weird “aha!” moment when I was in the studio with them and saw all this equipment — the facilities blew my mind. I was like, "What major is this?" They told me they were photography majors, and I knew immediately, "I'm going to go for that."

My first day of school was setting up a four-by-five camera. As a transfer student, they gave me no direction. I got a packet that said, "You go to RIT now." I showed up. The kids who went there, they took photography at specialized high schools before and were a little pretentious. Most of them don't do photography now. It's ironic.

When you were looking at work during your time in college and GQ, those were all mostly white photographers, right?

GQ was Mark Seliger, Peggy Sirota — they were all white.

Did you ever think, “I want to bring my own perspective to photography"?

Now that you ask me that, I don’t think so. This is a bigger conversation, but I've always had an identity crisis with not being Puerto Rican enough, and then also being really white. Sounding very American and purposely wanting to sound like that to be taken seriously. I didn't grow up with an accent, but I definitely grew up speaking Spanish — but that went away. Everyone in my family sounded and looked different. Seeing that reaction to them left an impression on me, "You need to sound grammatically correct and proper to be taken seriously." Maybe deep down, I always felt more white than Spanish.

In those moments, I didn't really put it together. Only in hindsight, especially last year, I started to realize everyone I met in the editorial world was white. It hit me now — I think I was trying to adapt and be included.

In those moments, I didn't really put it together. Only in hindsight, especially last year, I started to realize everyone I met in the editorial world was white. It hit me now — I think I was trying to adapt and be included.

Did you still feel connected to your Puerto Rican heritage when you were moving all over the world in these spaces? Or is it something where you feel like this identity where you're able to thrive wherever you go?

I would say the latter, what you said. Again, only now can I recognize this in hindsight. I've been trying to find myself and understand myself through seeing other places — I felt like I was adapting and that I had no connection with Puerto Rico. That made me feel really guilty.

You're not alone. So much of what you said resonated for me because of being in school and a lot of conditioning, I can speak Spanish, but when I respond to my parents, it's in English. I’ve accepted that this is not by accident — that in order to assimilate in the spaces I was in, I wasn't really encouraged to speak Spanish, because I was also surrounded by white people. Who am I going to speak Spanish to? [laughs].

When I started visiting Mexico in 2017, I felt like I was home. To be fair, I've never been to another Spanish-speaking country. I went to Spain once for work in 2013, but that was some other shit. That’s when I started thinking about going to Puerto Rico, but it always felt so daunting because my mom never talked about living there.

How was it photographing in Puerto Rico while also dealing with deeply personal family history?

I started emailing my biological father, who lives in Puerto Rico, after he emailed me out of nowhere in 2016. Every year, I was like, "He seems trustworthy, maybe I should go," but I kept pushing it off.

Then Hurricane Maria happened and I didn't hear from my dad for a while. I thought, "Man, if I don't do it now, who knows? My dad is 73."

My dad lives off the grid. He doesn't have a phone. He doesn't drive. He rides a bike and works at the University of Puerto Rico. When I got there, I didn’t even know if he was home. I knocked on the door — it was a typical little screen door. I saw some woman's feet. She came to the door and I started speaking in my half-assed Spanish.

I said, "Yo no se — la casa” (“I don’t know — the house”), and she immediately started to cry. I started to cry. I was like, "Oh my God, I'm at the house." Four seconds later, she said, "Mira quién está aquí!” (“Look who’s here!”), and my dad pulled up on his bike. He looked like he was going to have a heart attack.

I said, "It's me," and he was in shock. Then he came up and hugged me. That felt so weird to me — who's this older man, hugging me?

There wasn't enough time in those four weeks — four weeks went fast. Between staying with my dad, seeing aunts I haven't seen and cousins, and driving to the south for three hours with my friend, it was a blur. I really needed six months there. This was before COVID. I thought I’d be back in a few months and I'd stay for longer. That didn't really happen.

Then Hurricane Maria happened and I didn't hear from my dad for a while. I thought, "Man, if I don't do it now, who knows? My dad is 73."

My dad lives off the grid. He doesn't have a phone. He doesn't drive. He rides a bike and works at the University of Puerto Rico. When I got there, I didn’t even know if he was home. I knocked on the door — it was a typical little screen door. I saw some woman's feet. She came to the door and I started speaking in my half-assed Spanish.

I said, "Yo no se — la casa” (“I don’t know — the house”), and she immediately started to cry. I started to cry. I was like, "Oh my God, I'm at the house." Four seconds later, she said, "Mira quién está aquí!” (“Look who’s here!”), and my dad pulled up on his bike. He looked like he was going to have a heart attack.

I said, "It's me," and he was in shock. Then he came up and hugged me. That felt so weird to me — who's this older man, hugging me?

There wasn't enough time in those four weeks — four weeks went fast. Between staying with my dad, seeing aunts I haven't seen and cousins, and driving to the south for three hours with my friend, it was a blur. I really needed six months there. This was before COVID. I thought I’d be back in a few months and I'd stay for longer. That didn't really happen.

You described it as a blur. When you look through photos that you took during that time, does it become clearer? Do you notice what you were drawn to or how did photography help you?

Photography for me, it's like armor, it helps me disassociate.

I'm a very stimulated person, visually. I’m constantly scanning — ”there's a picture, there's a picture, there's a picture.” When we would drive through these abandoned areas, I was stunned. "Whoa, we drove past six pictures of blown-out windows or a destroyed house.” Then I would have to remember this used to be someone's home.

I'm a very stimulated person, visually. I’m constantly scanning — ”there's a picture, there's a picture, there's a picture.” When we would drive through these abandoned areas, I was stunned. "Whoa, we drove past six pictures of blown-out windows or a destroyed house.” Then I would have to remember this used to be someone's home.

Much of your work is looking, observing other people's lives. Did you have your camera with you the day you met your dad?

I always have my Contax 35 millimeter on me. I wanted to take a picture of my dad, but it actually felt very awkward. I would bring up the camera and I couldn’t do it.

Before I met my dad, I'd always look at kids on the train with their dad — little girls hugging them and stuff like that — and I'd be very envious. I wanted to know what that was like. So when I had that moment, I had a wall up for the first week. Then it started to break, but, of course, we started getting close when it was time to go. The day I left is when I first heard about COVID. It was January 30.

Before I met my dad, I'd always look at kids on the train with their dad — little girls hugging them and stuff like that — and I'd be very envious. I wanted to know what that was like. So when I had that moment, I had a wall up for the first week. Then it started to break, but, of course, we started getting close when it was time to go. The day I left is when I first heard about COVID. It was January 30.

Oh my gosh.

I'm crying telling this story, I was trying to talk to avoid crying. I think I haven’t processed the moment of meeting my dad yet.

Hearing you talk about all of this, I’m feeling so emotional. I was going through the photo series of images of your father, but hearing you talk about the process of meeting him and how it all came together leaves me feeling there is so much more to photograph.

The hard part of showing the relationship with my father in a photo series is, do these photos show that I didn't know this person before I came? How do you demonstrate that? I'm still struggling with the photo series.

There was a class nearby and I said, "I want to do this jiu-jitsu at six." He asked if he could come watch me. In my head, I was so excited, like a little kid. "Oh wow, my dad's going to see me do sports at 33!" He came, but I was very nervous he was going to leave — the whole time I was there, I kept looking at him in the corner. In my head, I was saying, "Please don't leave me. Please don't desert me."

It was funny because the people in the class kept asking "¿Es tu papa?" (“Is that your dad?”). I was like, "Well, I met him yesterday, but yes, it's my dad over there. I guess." It was cool because we could relate on one thing, the physicality. At the end, in the car ride home, he was so proud about it. He said, "Well, you're really good at this," and this and that. I never had that kind of coaching or encouragement before.

There’s a lot of things I still need to explore or ask about his life in general. Again, not possible in four weeks and going to the south of the island and photographing. I needed six months there.

There was a class nearby and I said, "I want to do this jiu-jitsu at six." He asked if he could come watch me. In my head, I was so excited, like a little kid. "Oh wow, my dad's going to see me do sports at 33!" He came, but I was very nervous he was going to leave — the whole time I was there, I kept looking at him in the corner. In my head, I was saying, "Please don't leave me. Please don't desert me."

It was funny because the people in the class kept asking "¿Es tu papa?" (“Is that your dad?”). I was like, "Well, I met him yesterday, but yes, it's my dad over there. I guess." It was cool because we could relate on one thing, the physicality. At the end, in the car ride home, he was so proud about it. He said, "Well, you're really good at this," and this and that. I never had that kind of coaching or encouragement before.

There’s a lot of things I still need to explore or ask about his life in general. Again, not possible in four weeks and going to the south of the island and photographing. I needed six months there.

What was your father’s reaction when you were taking pictures of him? What was the dynamic like once you introduced the camera and you told him that you are a photographer?

He did well with it. He was ready for it. He knew at that point what I could do — for four years, I would send my website or work. I think he was excited. Sometimes, I'd give him my camera, and I was like, "Take one of me," and it was nice.

Thank you for being open and for sharing all that.

I'm a very nostalgic person. I hate to say it, but I have a very difficult time not living in the past or thinking about all the times, all these moments we didn't have. It's hard to meet someone already old and envision what he would have been like if he was my dad. I liked him. I think it would have been better if it was a negative experience, and he was an asshole. But he was — I wouldn't say cool — but we had very similar personality traits that blew my mind from not living with this person. “We have the same temper. We have the same this, we have the same —"

It’s interesting how you brought up nostalgia because, for me, I'm always in the past. Maybe that’s why I am so drawn to photography and portraiture and family photos.

I was looking at your work and wondering, how is it that you approach photographing people? Is there a specific way that you approach people or a reason why you like taking portraits?

I was looking at your work and wondering, how is it that you approach photographing people? Is there a specific way that you approach people or a reason why you like taking portraits?

It's not one thing. I like taking pictures of the moments that happen in between. I like being a fly on the wall, I think that's another part of my disassociating thing but I definitely direct, and see the value of directing things.

"What am I doing with my photography? Am I evolving? Am I challenging myself? Is the portraiture getting better?" Yes, I'm in that world right now. I want to get better. I'm starting to lessen that anxiety of the comparing my work to things on Instagram, which is fucking impossible.

"What am I doing with my photography? Am I evolving? Am I challenging myself? Is the portraiture getting better?" Yes, I'm in that world right now. I want to get better. I'm starting to lessen that anxiety of the comparing my work to things on Instagram, which is fucking impossible.

In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

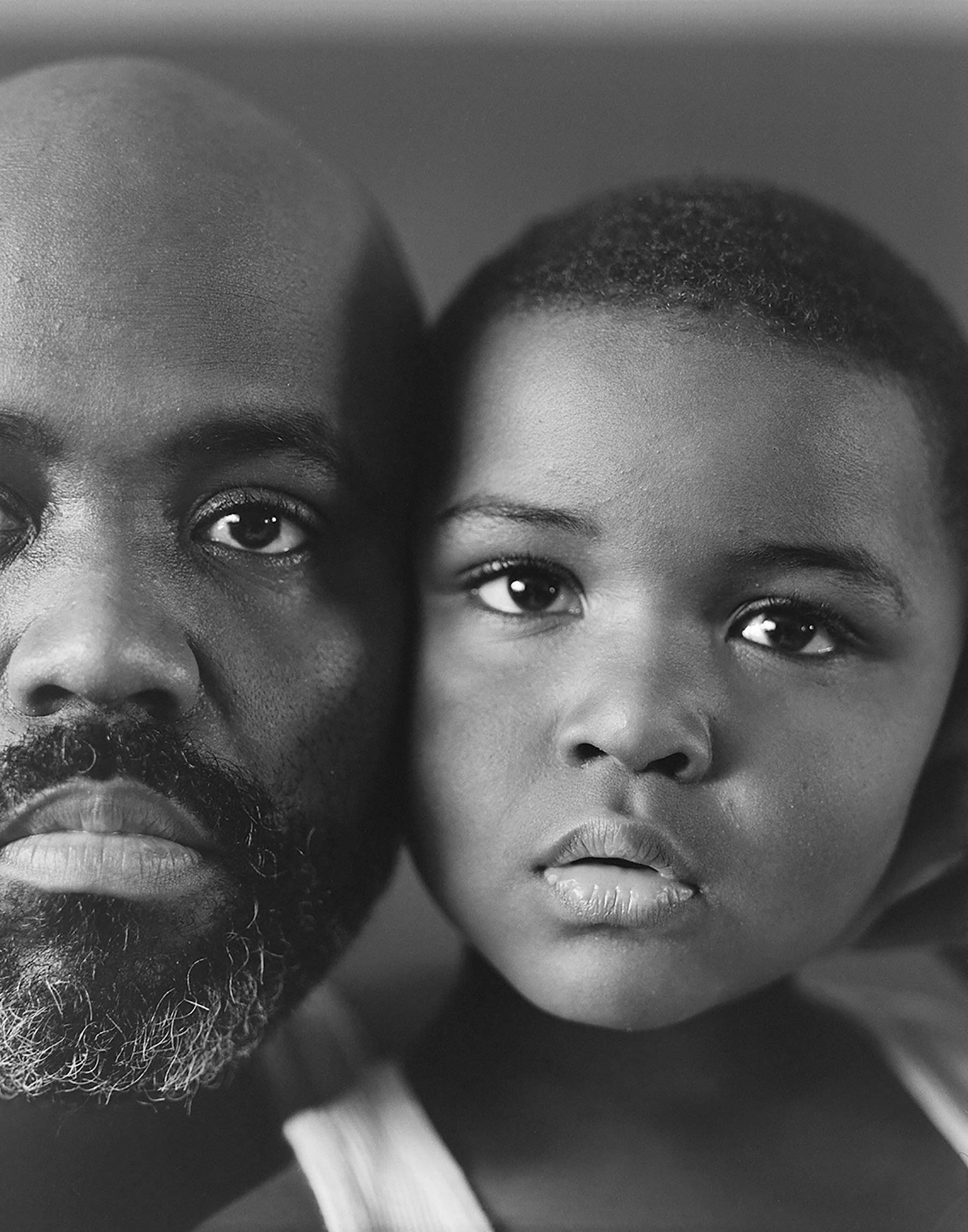

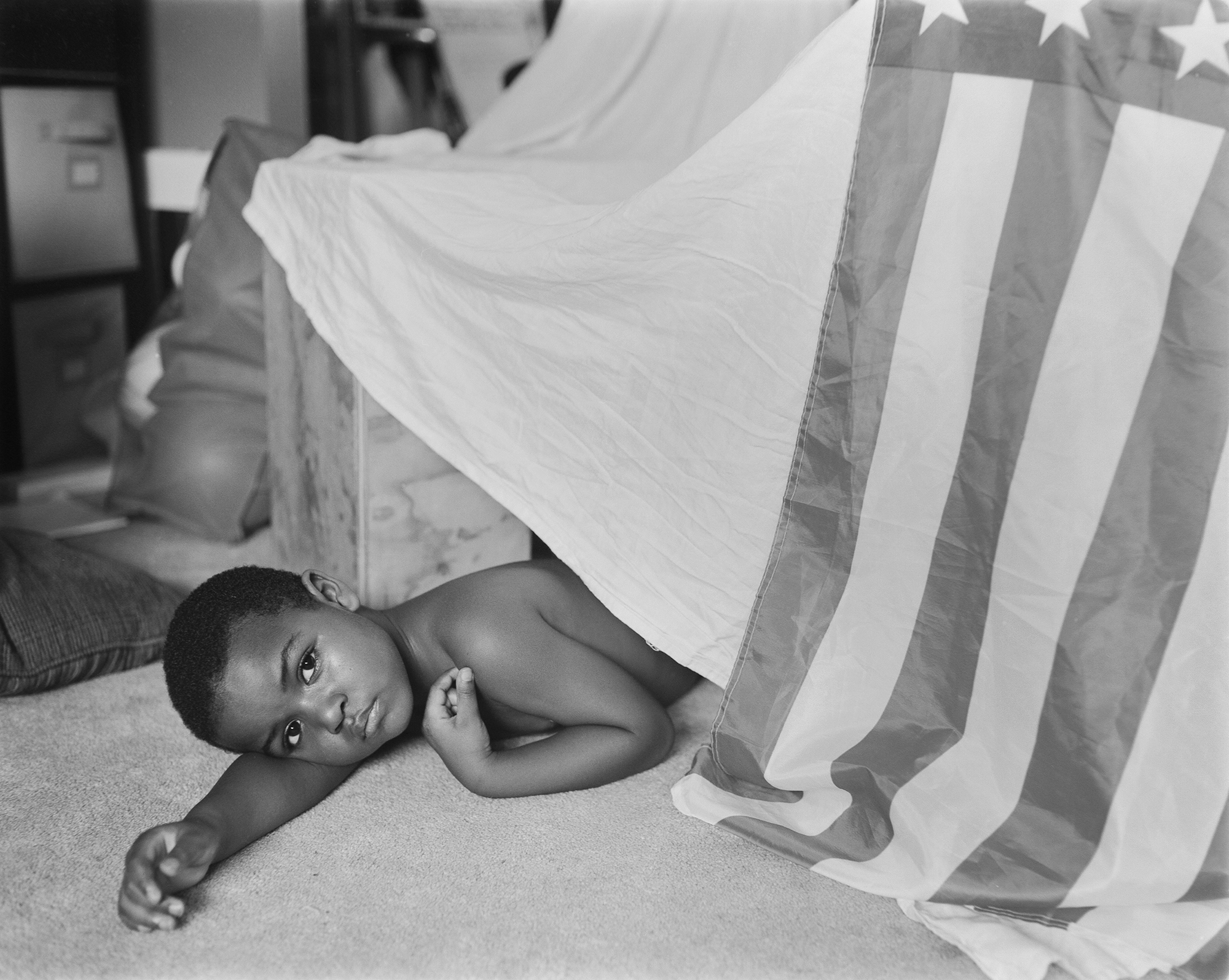

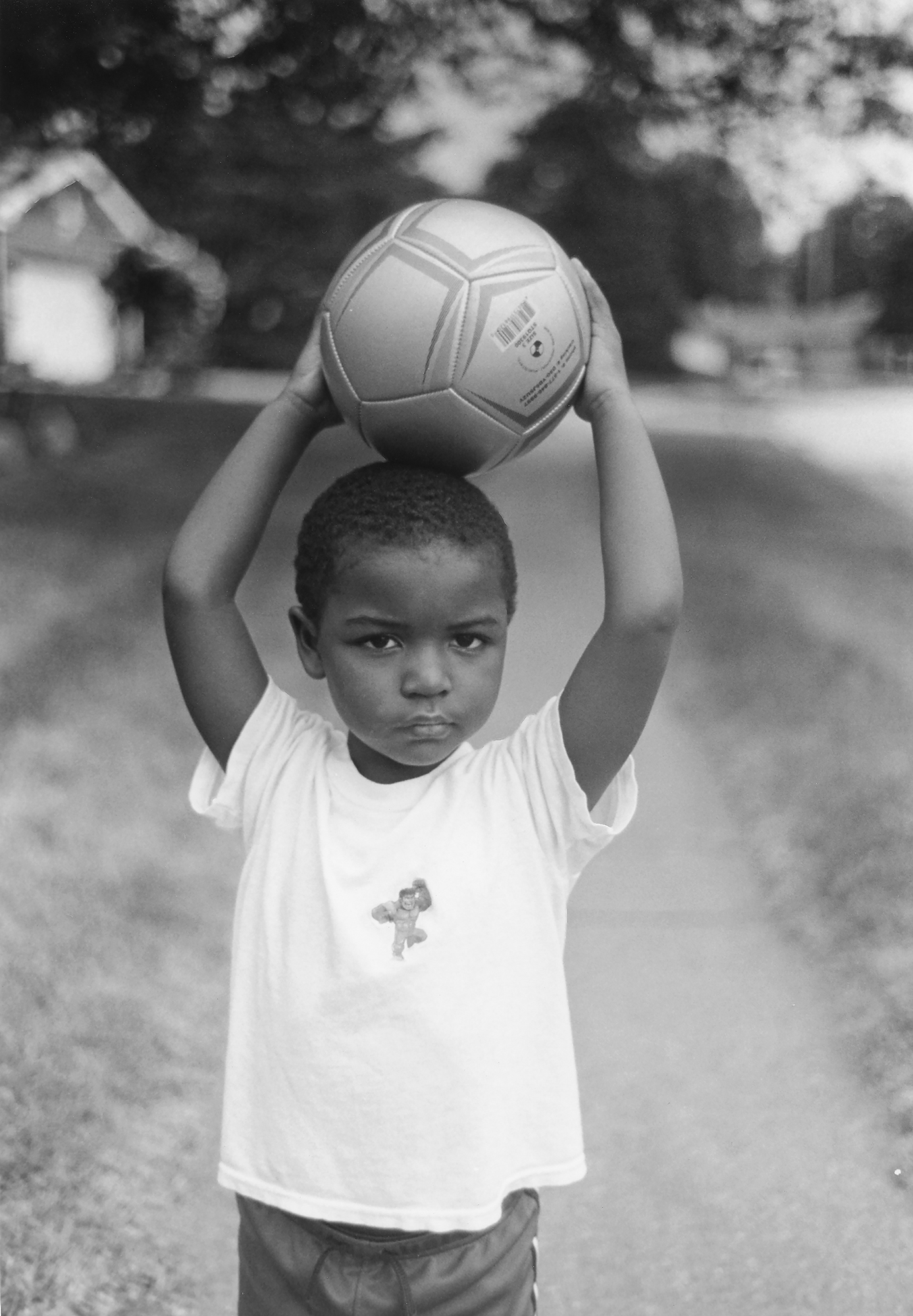

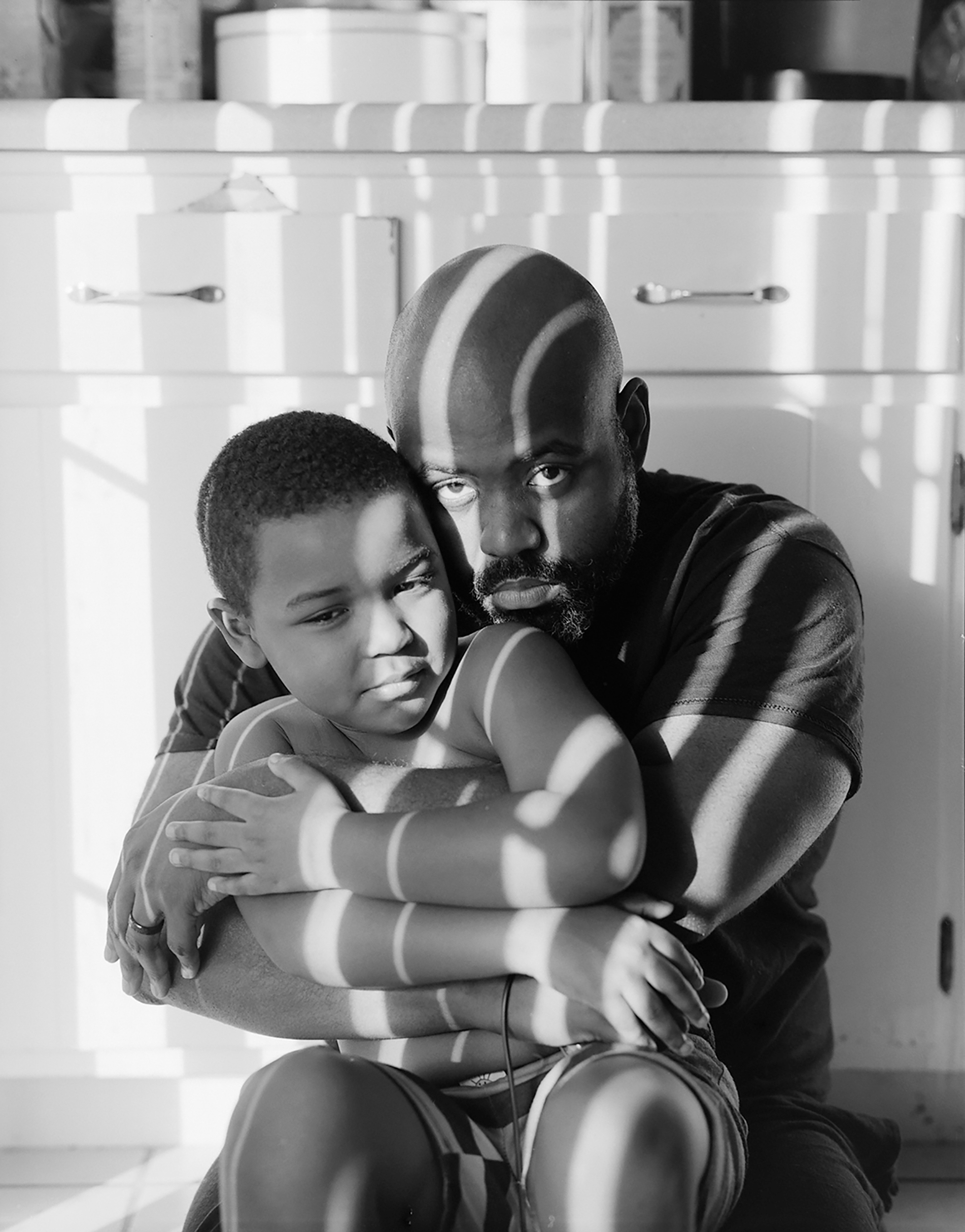

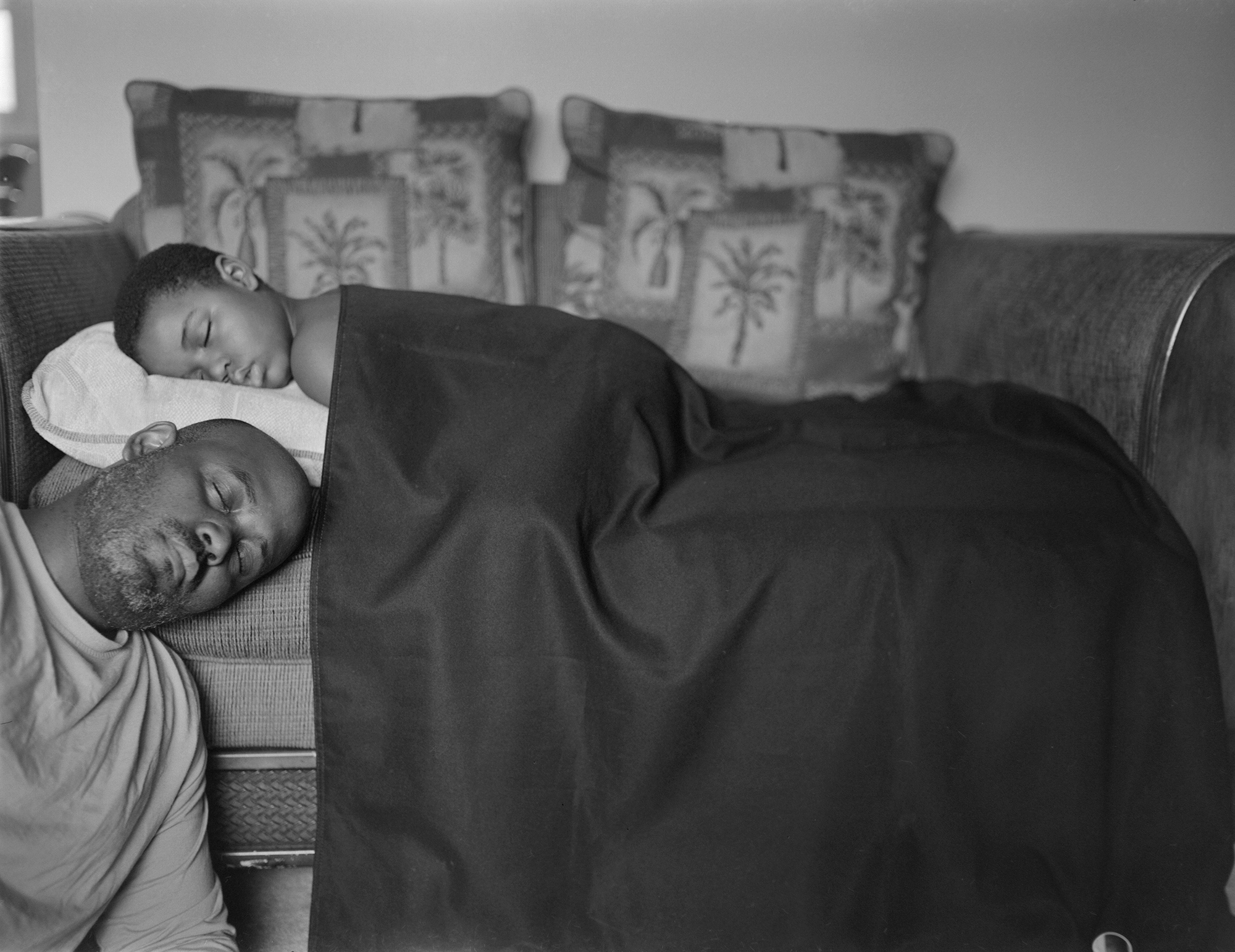

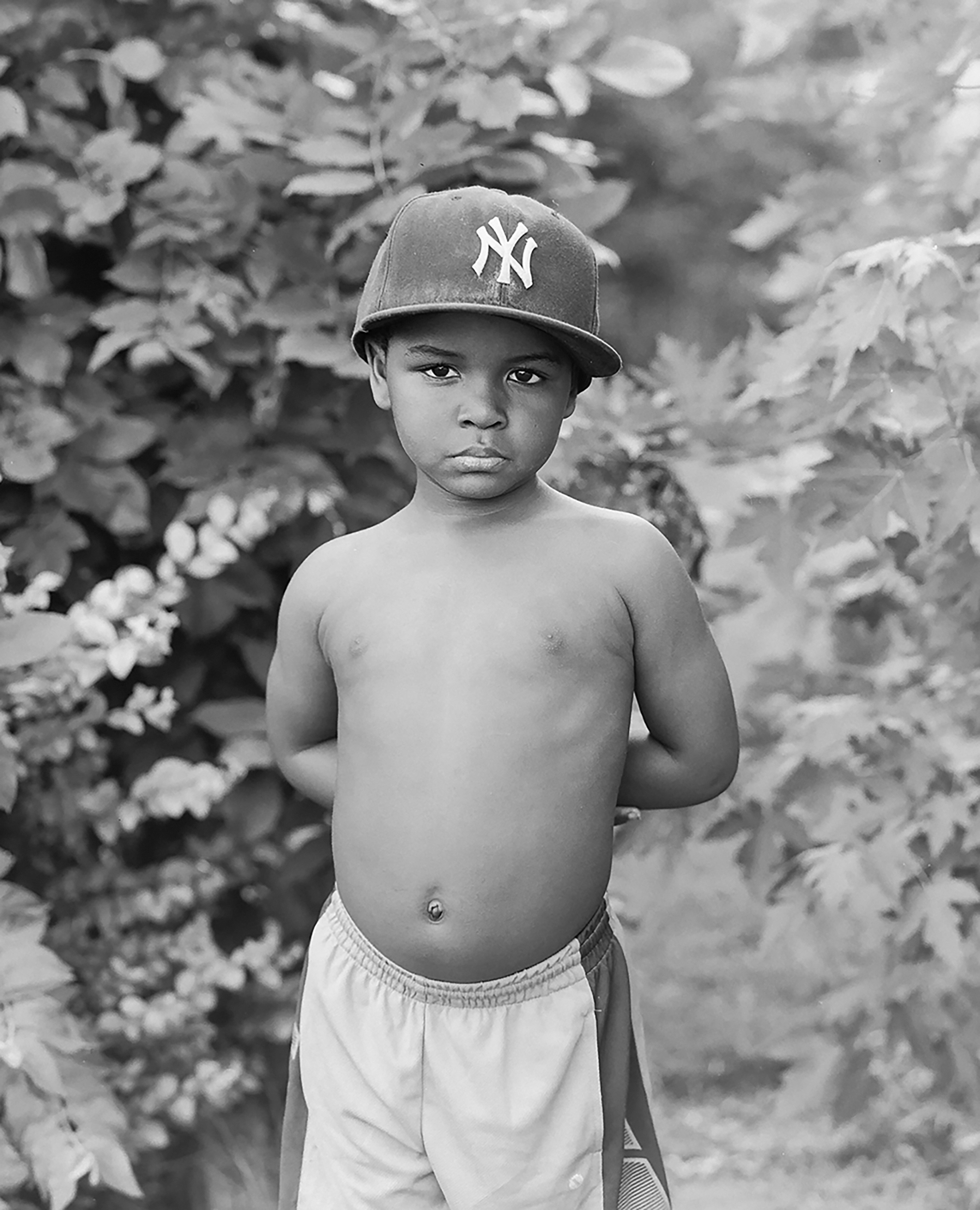

Rashod Taylor: Little Black Boy

I want to start by asking you who you are, where you're from, and where you currently are?

I’m Rashod Taylor from Bloomington, Illinois, where I currently reside.

I took an interest in photography early on, looking at family albums — my mom and dad always took pictures of every single thing. I still have their old Vivitar 35 mm camera around here somewhere. In high school, I did photojournalism for the school newspaper and yearbook. I ended up doing photography in college, graduating with an art degree with an area of specialization in fine art photography.

After college, there were no jobs for a fresh-out-of-college student who’s an artist, so I went back home after school. I worked a bit as an assistant for a commercial photographer and at a portrait studio, but then I got into financial services. I've been there ever since, but I've been doing photography throughout, so I never stopped making images. It’s something I do outside of my 9 to 5.

I took an interest in photography early on, looking at family albums — my mom and dad always took pictures of every single thing. I still have their old Vivitar 35 mm camera around here somewhere. In high school, I did photojournalism for the school newspaper and yearbook. I ended up doing photography in college, graduating with an art degree with an area of specialization in fine art photography.

After college, there were no jobs for a fresh-out-of-college student who’s an artist, so I went back home after school. I worked a bit as an assistant for a commercial photographer and at a portrait studio, but then I got into financial services. I've been there ever since, but I've been doing photography throughout, so I never stopped making images. It’s something I do outside of my 9 to 5.

It's incredible to see you producing this amazing work while knowing you also have many other things going on. Can you talk a about the project you've been working on, photographing your son? When did it start, and what your intention behind it is?

It started with being a first-time father. LJ, my son, is five. I began making photographs when he was born, with a 35 mm camera — the standard dad photos. You take pictures of everything your kids do, essentially. I started to look through all those images, and it dawned on me. There's many things in the photographs — whether it’s the way he's juxtaposed against another kid or what he's wearing or what he's doing — there's nothing in there that you wouldn't see a kid do. But I saw this thread that I wanted to show what it is to be a little Black boy because, on the surface, it's a lot of the same things any kid would do; however, he sees things a different way than other kids. I have to help him learn how to navigate life — in general and as a Black and Dominican boy. As a person of color and what that looks like in this world.

I started adding different elements in the images that go along with that journey. It's called Little Black Boy. It's about him, but at the same time, I'm dealing with my insecurities and vulnerabilities as it pertains to raising him. That comes through in some of the imagery. It's this real investigation of his childhood growing up Black in America, and me navigating fatherhood and parenthood, and, in a way, feeding off each other.

Every image is not necessarily an image where there's this super-deep underlying meaning, but then there's a lot of pictures that are. Some of the photos are light and reminiscence of childhood. I like that dynamic. I try to do a little bit of both and mix it up a little bit.

I started adding different elements in the images that go along with that journey. It's called Little Black Boy. It's about him, but at the same time, I'm dealing with my insecurities and vulnerabilities as it pertains to raising him. That comes through in some of the imagery. It's this real investigation of his childhood growing up Black in America, and me navigating fatherhood and parenthood, and, in a way, feeding off each other.

Every image is not necessarily an image where there's this super-deep underlying meaning, but then there's a lot of pictures that are. Some of the photos are light and reminiscence of childhood. I like that dynamic. I try to do a little bit of both and mix it up a little bit.

I was going to ask about the process you have in terms of the type of camera you use — and how did you keep your son still?

4x5 large format camera, some black and white film. It helps slow me down and take my time, compose an image, look at the light, and put something that I like together in the ground glass. It helps with LJ, too. Early on, it was more challenging because he was three, three-and-a-half. Most of the images on my site, he's probably four in all of these. There are some earlier images that I shot more with a medium format. That's a little easier, he's still four in some of these, so it's a matter of knowing what I want and getting him to do it. "Hey, sit right here, and read this book," or "Sit down for a minute." I get myself together and try to talk to him to keep him occupied.

At this point, he knows that we're going to take a photograph, and he does well at sitting and knowing — he's like, "Okay, Daddy, I'm ready for the picture. Go get your big camera.” I’ve got him pretty well-conditioned at this point. It was a lot more challenging at first, but now he's gotten into his own groove — he’s a good little actor.

At this point, he knows that we're going to take a photograph, and he does well at sitting and knowing — he's like, "Okay, Daddy, I'm ready for the picture. Go get your big camera.” I’ve got him pretty well-conditioned at this point. It was a lot more challenging at first, but now he's gotten into his own groove — he’s a good little actor.

Your work is so powerful. It's personal, and it's your son, but I see my own family when I look at these pictures. That's why I love the work so much. I see such tenderness and fragility. Did you see images like that of people who looked like you when you were growing up? Where did this vision come from?

We see some things in terms of Black life when looking at Gordon Parks and others, but honestly, there's not really any imagery depicting that. One of my influences and inspirations is Sally Mann. I enjoy her work, but then you think, "Well, I don't see any people of color making work like that."

I try to keep things simple — I want to focus on the everyday. I feel like that's where I make the best art, when I focus on the things I love and am passionate about. Photographing everyday life is heightened because it's a Black man photographing his son, which happens, but it's not mainstream in society. A lot of it has to do with people not having any exposure to it. When people interact with the work, it's like, "Wow, this is touching." You don't often see those types of images. It’s more of the opposite — you see the negative connotations and negative stereotypes of the Black family in general, of Black males and Black women. It was important to show the truth.

That truth has always been there. You know that, I know that. It's not like when you’re Black, you do different things growing up as a kid — we go on vacations. We play outside. We have friends. We go to our grandparents' house. We wear our parents' clothes. We do all of those things, but in society, no one takes the time to see who you are, that we're here and that we matter. All that's in the work, with some of my fears sprinkled in that go with his life and what I'm feeling.

I try to keep things simple — I want to focus on the everyday. I feel like that's where I make the best art, when I focus on the things I love and am passionate about. Photographing everyday life is heightened because it's a Black man photographing his son, which happens, but it's not mainstream in society. A lot of it has to do with people not having any exposure to it. When people interact with the work, it's like, "Wow, this is touching." You don't often see those types of images. It’s more of the opposite — you see the negative connotations and negative stereotypes of the Black family in general, of Black males and Black women. It was important to show the truth.

That truth has always been there. You know that, I know that. It's not like when you’re Black, you do different things growing up as a kid — we go on vacations. We play outside. We have friends. We go to our grandparents' house. We wear our parents' clothes. We do all of those things, but in society, no one takes the time to see who you are, that we're here and that we matter. All that's in the work, with some of my fears sprinkled in that go with his life and what I'm feeling.

It's a powerful act, to document your family and share it. It’s going to impact the way people see what family looks like, what childhood looks like, what Black parenting looks like. I wonder how different it would be if it was someone outside of your community or someone coming in from the outside and photographing your family? How different those pictures would be versus you creating the work yourself?

That's an interesting thought. I think you're 100% right, it would be very different. Different photographers have a way of making great images with people they meet, right? However, I think there's this intimacy and presence when dealing with the people you truly love and who are part of your family. It takes the images to the next level because I care and love them so deeply that — I hope — that comes through with the images. I think about him and I try to help him navigate this life and show that through the series.

Is documenting your son something that you're continuing to do?

Yes. It's an ongoing project. I will be working on it for a while, at least another five to seven years. I want to capture him as he's going through childhood. I'm sure at a certain point, he may not want anything to do with me — that's fine, I'll stop, but up until that point, I'm going to keep shooting. For this project, I'm looking to have a book in as he gets to that past-childhood phase and early adolescence — definitely by his teenage years.. It will have a different meaning at that point. It won't have the innocence that I'm interested in, but I'm excited because I hope to turn it into more once it's a finished piece of work.

I wanted to ask you how does being a Black artist inform your work?

I will say this — it's a huge part of my photography per se, but I like the fact that other Black photographers may not have that as a part of their practice and are interested in other things. I think, sometime we get typecast: "Oh, he's a Black photographer or she's a Black photographer, so they have to photograph the struggle or racism," and those might be only the jobs they get or that's how people see them.

I believe that we can do anything we want to do, but it does include this work for me. It's the life I live every day, so it's honest and it's truthful — whether I like it or not, it comes out. Specifically, in this series, that plays a huge role in my son’s upbringing, and obviously a huge role in me being a father, a parent, a husband living in America.

I've come to a point where I've embraced it. It's one of those things where you get in those conversations with people and they act like you’re the spokesperson, and you’re not — I'm not speaking for all Black people. I'm not speaking for all Dominicans. At the same time, it is this way that we — people of color — are representative of the larger group, and since we haven't had that voice in so long, and it's been downtrodden and overlooked, I feel responsible for making sure that since this work has to do with that. I want to have it amplified as much as possible because many people can identify with it. It has that way of connecting with people, and I think that is good in terms of continuing these conversations on racism and injustice.

I believe that we can do anything we want to do, but it does include this work for me. It's the life I live every day, so it's honest and it's truthful — whether I like it or not, it comes out. Specifically, in this series, that plays a huge role in my son’s upbringing, and obviously a huge role in me being a father, a parent, a husband living in America.

I've come to a point where I've embraced it. It's one of those things where you get in those conversations with people and they act like you’re the spokesperson, and you’re not — I'm not speaking for all Black people. I'm not speaking for all Dominicans. At the same time, it is this way that we — people of color — are representative of the larger group, and since we haven't had that voice in so long, and it's been downtrodden and overlooked, I feel responsible for making sure that since this work has to do with that. I want to have it amplified as much as possible because many people can identify with it. It has that way of connecting with people, and I think that is good in terms of continuing these conversations on racism and injustice.

I want to advocate for artists of color, I'm sick and tired of them only getting assigned certain things, whereas white counterparts get the benefit of the doubt to shoot anything or any race. Why is that? I find such inspiration when I meet with artists like you who are doing artwork in a way that is so true to their lived experience. Your work is inspiring a lot of people. I hope you know that. I get emotional looking through all of your photography.

Thank you. I appreciate that. You got me. I was speaking at a conference, and I definitely was emotional — the tears were coming out of me. It was recorded, too. I'm like, "Oh gosh. Let me get through this before crying."

In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

Luis Manuel Diaz:

Portfolio Overview

This body of work is a collection of what I thought were two separate projects, but have recently come to realize that they need each other in order further contextualize my lived experience. The images were created in the US, where I immigrated to, and of Mexico, where I immigrated from. These works investigate what happens post-migration, what happens to a family when they're reunited in the US, how does one adapt to a new landscape and way of life? What happens to the home you leave behind, who is left behind, who takes care of the landscape that housed previous generations? The images attempt to provide two perspectives on what immigration is and what are causes and effects, that create both of those landscapes.

Beautiful. I love that. I was first introduced to your work at the Bronx Documentary Center, the imagery shot in your hometown of Mexico, and your family’s images in the United States — they were both connected, but there were also remarkable differences visually. I think it would be interesting to showcase a mix of both.

My use of black and white and color photographs came about wanting to challenge the master narrative surrounding immigration and how we view images in general. When we think about memory, traditionally it's been shown as black and white and super moody. But for me, memory — especially memory of home — is vibrant. That's why my images of Mexico are so vibrant and super specific. They're specific images about locations, objects, textures, smells, and of course my grandparents.

All of my images in the US are intentionally black and white. I was initially interested in the history of photography and how images became a colonist tool to promote white supremacy. I wanted to create images that would counter those narratives that had been created for us with the same tools — a camera and black and white film. But eventually it started speaking to this different view about both halves of these spaces, how the black and white images were more real but harsher, and the color images were softer but more aesthetically pleasing.

In my opinion, when people immigrate and leave for a long time, when we think of home, we tend to aestheticize home — we long for this beautiful place. We seem to forget why we left, but we remember everything that's left behind, the more beautiful things about the space. But once you're back there and you have the privilege to go back to these spaces, it takes time for you to realize that it's no longer a place for you. Well, at least personally, it wasn't a place where I could thrive, socially or economically.

All of my images in the US are intentionally black and white. I was initially interested in the history of photography and how images became a colonist tool to promote white supremacy. I wanted to create images that would counter those narratives that had been created for us with the same tools — a camera and black and white film. But eventually it started speaking to this different view about both halves of these spaces, how the black and white images were more real but harsher, and the color images were softer but more aesthetically pleasing.

In my opinion, when people immigrate and leave for a long time, when we think of home, we tend to aestheticize home — we long for this beautiful place. We seem to forget why we left, but we remember everything that's left behind, the more beautiful things about the space. But once you're back there and you have the privilege to go back to these spaces, it takes time for you to realize that it's no longer a place for you. Well, at least personally, it wasn't a place where I could thrive, socially or economically.

My family came from the Dominican Republic, but anytime I'm back there, or remember being there, I think of all the colors of vibrancy, the noises and longing for that and what a contrast that is to America in a lot of ways. Tell me about your background. Where is your family from? And your immigration story.

My family history — specifically immigration — started with my maternal grandfather. He was part of the Bracero program — he came to the US in the 50s and worked in the fields picking grapes, apples, potatoes. He did everything, a lot of field labor. The Bracero program was initiated in the 1940s by the United States, where they could hire seasonal Mexican workers for cheap, manual labor. It was through the Bracero program that there was this first iteration of the American dream for my family.

That first American dream was to come to the US to work, save money, go back home, and buy property. And that was what my grandfather did. He bought a huge piece of land where he raised cows, farmed and re-imagined it for future generations. But later on, this American dream changed. The next generation — my father and mother's generation — they thought they could work the land in Mexico in these larger pieces of fertile land, but because of NAFTA, farm work was no longer profitable — it was back to trying to make life in America on their own.

Ever since my father was a teenager in the early 80s, he immigrated to the US and worked for years as a farm worker, gardener, and construction worker. As an undocumented immigrant he wasnt able visit home much, but would try to visit once a year. Later on he was able to become a “legal” resident through Reagan’s amnesty in 1986 — one of the few amnesties that the States has done.

I was born and raised in Mexico and all through my childhood, my father would come and go. I would only see him for a month during the holidays, and that would be it. And then the occasional phone calls when he would get out of work and we would get to talk to him for a few minutes. That was our life. I didn't realize how horrible it was until I got older. Growing up, I thought that was the norm. I thought everyone experienced this because everyone in our community went through the same thing. All the fathers would be away and we would have all these mother figures taking care of all the kids.

That was our life up until I was nine years old. It took my father years and thousands of dollars in order for us to reunite. (People need to understand that it's extremely difficult and expensive to get a greencard, and not only that but it takes years before all paperwork is approved and you can reunite with your family.) In 2006, we immigrated to the US and for the first time in our life we could enjoy each other's presence without a ticking clock in your head. After immigrating and reuniting, survival mode was activated. That's when we're trying to adapt to this new environment and assimilation hits — you'd go through this out-of-body experience, trying to find people you can relate to. But you can’t relate to anyone, so you start changing to fit in and all these existential issues that immigrants go through while trying to adapt to this new environment.

That first American dream was to come to the US to work, save money, go back home, and buy property. And that was what my grandfather did. He bought a huge piece of land where he raised cows, farmed and re-imagined it for future generations. But later on, this American dream changed. The next generation — my father and mother's generation — they thought they could work the land in Mexico in these larger pieces of fertile land, but because of NAFTA, farm work was no longer profitable — it was back to trying to make life in America on their own.

Ever since my father was a teenager in the early 80s, he immigrated to the US and worked for years as a farm worker, gardener, and construction worker. As an undocumented immigrant he wasnt able visit home much, but would try to visit once a year. Later on he was able to become a “legal” resident through Reagan’s amnesty in 1986 — one of the few amnesties that the States has done.

I was born and raised in Mexico and all through my childhood, my father would come and go. I would only see him for a month during the holidays, and that would be it. And then the occasional phone calls when he would get out of work and we would get to talk to him for a few minutes. That was our life. I didn't realize how horrible it was until I got older. Growing up, I thought that was the norm. I thought everyone experienced this because everyone in our community went through the same thing. All the fathers would be away and we would have all these mother figures taking care of all the kids.

That was our life up until I was nine years old. It took my father years and thousands of dollars in order for us to reunite. (People need to understand that it's extremely difficult and expensive to get a greencard, and not only that but it takes years before all paperwork is approved and you can reunite with your family.) In 2006, we immigrated to the US and for the first time in our life we could enjoy each other's presence without a ticking clock in your head. After immigrating and reuniting, survival mode was activated. That's when we're trying to adapt to this new environment and assimilation hits — you'd go through this out-of-body experience, trying to find people you can relate to. But you can’t relate to anyone, so you start changing to fit in and all these existential issues that immigrants go through while trying to adapt to this new environment.

Thank you so much for sharing that with me, because it is important for people to understand the process and nuances that happen with immigration. And what happens with family history and assimilation is a huge part of our lives as immigrants. It's something that I'm starting to unravel myself because I was born and raised here, it's not something I ever even questioned. It was just like, “you have to assimilate, this is what you do.” Did you see any images when you were growing up that you felt reflected your experience?

Coming from a place like Mexico where I’m on the lighter side of a mestizo, I had the privilege of seeing a version of myself represented — TV was filled with the light skin mestizos and white Latinos. But when I came to the United States, I quickly lost that representation. I soon started to experience displacement, I went from seeing myself in mass media to not seeing myself at all. And I went through a lot, because of assimilation and the toxicity that comes along with it.

It took me until later in high school that I became self aware of my actions and began to think critically of the consequences of assimilation. It took some time to unlearn who I thought I was, and relearn who I wasn't allowing myself to be. It was through my initial stages of “decolonizing the mind,” that I remember reading articles about biculturalism, and it's importance — specifically for immigrant youth. This meant allowing myself to be part of both cultures and not having to choose one or the other, yet remaining true to my roots. Something thats not really talked alot about in our community is mental health, immigrants specially young immigrants and kids of immigrants go through severe mental health issues brought by assimilation and displacement. And that is why representation matters, when someone feels seen and their experiences validated they no longer feel alone.

When I began to explore identity politics in my practice I had a very hard time finding work that spoke about my experience. Later on as an undergrad I was introduced to work by Latoya Ruby Frazier, Laura Aguilar, and Deana Lawson — these innovative artists addressing critical issues about race, family, diaspora, immigration and care. Though their work did not directly address my experience, it provided a fundamental foundation in my image process. Seeing that work grounded me and guided me and ultimately gave me the confidence in how I wanted to approach my narrative reclamation.

It took me until later in high school that I became self aware of my actions and began to think critically of the consequences of assimilation. It took some time to unlearn who I thought I was, and relearn who I wasn't allowing myself to be. It was through my initial stages of “decolonizing the mind,” that I remember reading articles about biculturalism, and it's importance — specifically for immigrant youth. This meant allowing myself to be part of both cultures and not having to choose one or the other, yet remaining true to my roots. Something thats not really talked alot about in our community is mental health, immigrants specially young immigrants and kids of immigrants go through severe mental health issues brought by assimilation and displacement. And that is why representation matters, when someone feels seen and their experiences validated they no longer feel alone.

When I began to explore identity politics in my practice I had a very hard time finding work that spoke about my experience. Later on as an undergrad I was introduced to work by Latoya Ruby Frazier, Laura Aguilar, and Deana Lawson — these innovative artists addressing critical issues about race, family, diaspora, immigration and care. Though their work did not directly address my experience, it provided a fundamental foundation in my image process. Seeing that work grounded me and guided me and ultimately gave me the confidence in how I wanted to approach my narrative reclamation.

That's what moves me so much about your work, because it is a real direct challenge to how immigration — specifically Mexican immigration — is typically depicted. To me, it’s a meditation on what it means to navigate different cultures, and that's what we need more of — what it means to live our identities and aspire for the American Dream in a quiet, thoughtful way. A lot of the imagery I've seen about immigration is not subtle work. People need to understand the complexity behind all these stories and our families.

Historically speaking, in photography, immigrants are either criminalized or victimized. That was part of my frustration, trying to find myself and what work I wanted to see — I wanted to make images about the everyday. I wanted to make images that broke away from this master narrative surrounding immigration. Part of that was I wanted to share these intimate moments that I knew were happening but weren't being talked about. What does it mean to take care of your family? What does it mean to reconnect with your family? Because you lose connection when you immigrate, you assimilate, you lose that connection, but what happens when you go back and try to connect — or, more literal, reconnect — when you're separated and get back together, trying to get to know each other again.

I wanted to create images to speak of our everyday life that people don't tend to assume happened. Especially when people think about Latino men — there's more tender moments. My dad, he can seem like an intimidating guy, but he just doesn't like smiling. He's serious in a lot of pictures, but he's sweet and tender and caring — especially with my mother now that he’s no longer working. He’s handicapped due to a construction incident. My mother is essentially the breadwinner and he takes good care of her. He cooks for her, he cleans for her. He rubs her feet when she's tired — there are so many of these soft, gentle, deep moments that I want to shine a light on. There are also more complex issues when you're talking about identity — how do you see yourself within your family? How do I view myself with my older brother and my father — where do I play in between? Who am I? I am trying to disect what brings us together and what sets us apart.

I wanted to create images to speak of our everyday life that people don't tend to assume happened. Especially when people think about Latino men — there's more tender moments. My dad, he can seem like an intimidating guy, but he just doesn't like smiling. He's serious in a lot of pictures, but he's sweet and tender and caring — especially with my mother now that he’s no longer working. He’s handicapped due to a construction incident. My mother is essentially the breadwinner and he takes good care of her. He cooks for her, he cleans for her. He rubs her feet when she's tired — there are so many of these soft, gentle, deep moments that I want to shine a light on. There are also more complex issues when you're talking about identity — how do you see yourself within your family? How do I view myself with my older brother and my father — where do I play in between? Who am I? I am trying to disect what brings us together and what sets us apart.

I'm blown away by your work. These are all taken on a large format film camera, 4x5, which is a whole process. It is not a handheld camera. It's not a process where you can quickly take a lot of images in a short amount of time. What is it like for you working with a 4x5 camera? How do you feel that informs the work that you're doing?

I initially started shooting 4x5 because it's a tool that slows you down and makes you think about the images you're creating. You have to question yourself, “Why am I creating this image?” It takes me anywhere from 15 to 20 minutes to create an exposure, to set everything up and adjust it. In a way, I like to think its a sneaky way that allows me to connect with my family and spend more time with them and really get to know them even more, especially when you're looking through the camera. It's also a testament to the care that goes into the work not only by the photographer but by the subject, someone that is willing to sit for that long truly cares for you and the work.

For me, it also goes back to the history of photography as I had mentioned. It's a camera that was used to colonize us and was used to create these false narratives surrounding us. I'm reclaiming the same tool to create new images, creating a new archive of images that talk about our experiences in a more adequate way.

For me, it also goes back to the history of photography as I had mentioned. It's a camera that was used to colonize us and was used to create these false narratives surrounding us. I'm reclaiming the same tool to create new images, creating a new archive of images that talk about our experiences in a more adequate way.

It’s a form of activism really. Reclaiming images of our family, of our culture and all while doing the medium, that for so long has oppressed us. I am excited for people to know this about your process, because it's something where if you're looking online you probably assume it's digital, right. When you're talking about your intentions behind this work for people to understand just how much work is going into this process.

Right — it just takes a lot of time and patience. For me, it's important for people to understand that there's a whole process behind making photos. There are images that I think about, and sketch out, but I still allow air to flow in between image making to create flexibility. There's also images that happen by complete accident, where everything aligns and you just press your shutter. It's also important to mention that my subjects also collaborators in the image process — specifically with my family work — because it's no longer my story, it's our family story. Between shooting we talk about visualization and how they want to be depicted or what they want the world to know about them.

Through this work, what do you want people to know about your family and about your lived experience?

I want them to know that even though I'm talking about my specific family, there's hundreds of thousands of families who are going through this — my story is just one of them. I want to invite the viewer to think about their own ideas of what immigration looks like and to challenge those ideas.

There needs to be more intersectionality when we talk about immigration, because it's not only about crossing borders, but it's also what happens when you get here. What happens to the rest of the family? There needs to be more conversations surrounding identity, trauma, care and mental health. That's something our community doesn't talk a lot about is mental health — even sexuality and all these other topics that just get swept under the rug when we talk about immigration.

There needs to be more intersectionality when we talk about immigration, because it's not only about crossing borders, but it's also what happens when you get here. What happens to the rest of the family? There needs to be more conversations surrounding identity, trauma, care and mental health. That's something our community doesn't talk a lot about is mental health — even sexuality and all these other topics that just get swept under the rug when we talk about immigration.

What are your hopes and dreams for the future in terms of your photography?

I want to get more people involved in my current series. I'm working on another side project where I work with more community members. I want to take it outside of my family and expand this narrative and get more stories into what it means to immigrate and talk with first generation Americans. I want to talk to kids of immigrants and what their experience is.

I would like to publish a book with my family work. Books for me in undergrad became so important because they were this physical source of knowledge that I could take. I want someone to eventually connect to my work, that they could go and spend time and look through my work — and my work becomes this widely available source for people.

I would like to publish a book with my family work. Books for me in undergrad became so important because they were this physical source of knowledge that I could take. I want someone to eventually connect to my work, that they could go and spend time and look through my work — and my work becomes this widely available source for people.

In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

INDUSTRY TALK with Oriana Koren

[Note to our readers: This is our first Industry Talk feature, where we dive in with artists and reflect on our experiences navigating the photography industry. A huge thank you to Oriana for their fierce candidness. - Sara]

Oriana, where would you like to start, what would you want our readers to know about you?

I grew up bilingual, speaking Haitian Creole and English. I come from a half-Black immigrant family, half-Black American family. For both groups, education is incredibly important, but specifically for West Indian and Caribbean immigrants — people who sacrifice a lot to leave the islands to come here to build better futures for their kids.

The Dominican Republic is where I am from, and Haiti shares the same island— what an interesting connection!

My mother copied her Haitian experience onto her American experience. This is a woman who comes from a country that's been colonized, so whether or not she can articulate it, she has an understanding of what it is like to live and move around in a world with colonizers as a colonized person. I think it was a comfortable, easy fit for her because certain things come with the idea of success, right? And for her American mind, it was, “My kids have to go to all the best schools from pre-K through college.”

The way that I approach my photographic work, it's with the same sort of rigor I learned in Montessori, in private prep, in the baccalaureate program. I've never been able to separate that kind of thinking and learning from making pictures.

The way that I approach my photographic work, it's with the same sort of rigor I learned in Montessori, in private prep, in the baccalaureate program. I've never been able to separate that kind of thinking and learning from making pictures.

In what ways has the industry failed you to the point where you are no longer interested in doing assignment photography? It's important for people in the industry to understand how their actions impact BIPOC creatives. Even if you have all the credentials, all the education, you're still confronted with so much racism.

I was talking to a friend about this yesterday. I'm not working in galleries because of this. And I decided I wasn't going to work as a wedding photography editor because I ended up getting fired from that job. Not because I did anything wrong, but because I became my boss’ target whenever she got pissed off about something. So her husband pissed her off one day and I ended up losing my job off of that.

I’ve gotten to the point where I can't do assignment photography anymore. Every time I have to invoice someone, some white person talks crazy to me about money that I worked hard for, that I earned — they talk to me as though I didn't earn that money, like I’m not entitled to that money. They act like I'm annoying them because I'm asking for money owed to me. Imagine having to do that every assignment for five years.

I’ve gotten to the point where I can't do assignment photography anymore. Every time I have to invoice someone, some white person talks crazy to me about money that I worked hard for, that I earned — they talk to me as though I didn't earn that money, like I’m not entitled to that money. They act like I'm annoying them because I'm asking for money owed to me. Imagine having to do that every assignment for five years.

The economics of it all is a huge part. Some artists do not have generational wealth and rely on their creative work as their main source of income. How do you feel about the hiring editors you’ve worked with previously? Do you feel they're informed about how they're assigning work?

I have a handful of Black and or non-Black of color editors I've worked with — it's a handful, maybe five.

I would say 98% of my work comes directly from white decision-makers and photo editors. That's when I started to recognize this might end up being a very similar situation to weddings, except you have to deal with lots of different people in lots of different places at lots of different companies.

But the one thing that's always been consistent is — and I hate to say it — this recent generation of photo editors is lacking all the way around. Many of them don't study photography. They don't do anything about it until they have a photo editing job. That's unacceptable.

I would say 98% of my work comes directly from white decision-makers and photo editors. That's when I started to recognize this might end up being a very similar situation to weddings, except you have to deal with lots of different people in lots of different places at lots of different companies.

But the one thing that's always been consistent is — and I hate to say it — this recent generation of photo editors is lacking all the way around. Many of them don't study photography. They don't do anything about it until they have a photo editing job. That's unacceptable.

That resonates with me I got a college degree in art history and photography. I put in years of work and study then to see people just waltz in: “Oh, this seems like an easy job and field to move into and not to hold people across the industry to any sort of standard!” It’s demoralizing. I have seen some incredibly horrible, lazy, complacent ways of doing work from extremely privileged and unqualified editors.

Privilege — yep. Last year

I shot my first national food magazine feature. I have been working for five years. I had to shoot two cookbooks before I got a national feature magazine. This is how backward the industry is when it comes to this idea that Black people especially have to prove that they should get the jobs.

I shot my first national food magazine feature. I have been working for five years. I had to shoot two cookbooks before I got a national feature magazine. This is how backward the industry is when it comes to this idea that Black people especially have to prove that they should get the jobs.

This is important to talk about. Who's given opportunities, and what is it based on?

Yes — for me, whenever it came for any sort of a job, if I didn't have examples of it in my portfolio, I would get passed on for assignments. Yet many white male photographers are just given the benefit of the doubt that their work is great: “We'll hire them!”

It's the sort of thinking that comes when you're a person who has not in any way, shape or form deeply engaged in intimate relationships with Black people. Because if these people were actually in a relationship with us, they would know our capacities and capabilities before assigning us to work.

It's the sort of thinking that comes when you're a person who has not in any way, shape or form deeply engaged in intimate relationships with Black people. Because if these people were actually in a relationship with us, they would know our capacities and capabilities before assigning us to work.

These practices of hiring the same photographers repeatedly is such a disservice to photography. This is the reason why people don't understand what photo editing is and don't take our work seriously — they think anyone can do our jobs because the industry is filled with people who never studied photography, express no interest expanding their understanding of art, and aren't capable of doing their jobs.

It makes it hard for me as a photographer to do my job properly. A lot of what is running me out of assignment photography is that they’re not paying me enough to do my job well. And they’re certainly not paying me enough to do my job, their job, and probably two or three other people's jobs.

Before assigning me work, there is a certain amount of work that they’re required to do as a photo editor. They don't get to then just push that off on their freelancers. And that's not specific to me as a Black freelancer. For the last six or seven years, all freelancers have been doing additional work because the photo editors they are working with are not trained.

By the time you are working as an assignment photographer and working on the front lines, you should be a master at your craft. That's what I was told you needed to be in order to get to those positions. So when I'm talking to people who've been in the business for years and I'm telling them shit that they don't know — that is unacceptable to me. You have the Pulitzers, you get $10,000 to speak at conferences, but you actually don't know anything about the medium or the genre you're working in? How does that happen?

I have to be the one who knows everything. I have to be able to speak in perfect paragraphs so people can quote me for their inclusion and diversity initiatives. And I get a pat on the back for being rigorous, but what's going on with Joe Blow? Why aren't you challenging him in that same way?

You're the person who's reading the images to decide whether or not it makes sense to the narrative that is being pushed, if it matches the text that it's being put next to, if it's going to cause any ethical or moral issues in terms of the general public viewing the imagery — these are the things that photo editors are supposed to be thinking about.

A lot of them are very lucky to be working with photographers who are already a step ahead and thinking that way, but that's not every photographer. And that's an issue for me — the number of people who are succeeding at this work, who don't care about it, who don't understand the medium’s history, who don't engage with the theory of the medium.

Before assigning me work, there is a certain amount of work that they’re required to do as a photo editor. They don't get to then just push that off on their freelancers. And that's not specific to me as a Black freelancer. For the last six or seven years, all freelancers have been doing additional work because the photo editors they are working with are not trained.

By the time you are working as an assignment photographer and working on the front lines, you should be a master at your craft. That's what I was told you needed to be in order to get to those positions. So when I'm talking to people who've been in the business for years and I'm telling them shit that they don't know — that is unacceptable to me. You have the Pulitzers, you get $10,000 to speak at conferences, but you actually don't know anything about the medium or the genre you're working in? How does that happen?

I have to be the one who knows everything. I have to be able to speak in perfect paragraphs so people can quote me for their inclusion and diversity initiatives. And I get a pat on the back for being rigorous, but what's going on with Joe Blow? Why aren't you challenging him in that same way?

You're the person who's reading the images to decide whether or not it makes sense to the narrative that is being pushed, if it matches the text that it's being put next to, if it's going to cause any ethical or moral issues in terms of the general public viewing the imagery — these are the things that photo editors are supposed to be thinking about.

A lot of them are very lucky to be working with photographers who are already a step ahead and thinking that way, but that's not every photographer. And that's an issue for me — the number of people who are succeeding at this work, who don't care about it, who don't understand the medium’s history, who don't engage with the theory of the medium.

I have seen many people with hiring power throw money and assignments at their privileged friends who don’t need it — that's money and opportunity a different artist could have. I think there's a disconnect of not understanding how that perpetuates racism and furthers the gap.

What makes this moment in time interesting is about five months ago, we all found out that we were broke. I know lots of people in the industry who, because of the way they were curating their Instagrams and because of what they were telling and what they were omitting, seemed like they were doing pretty good. And then the economy fails and we're told that we can't go to work. And all of a sudden everybody doesn't have money, which means no one was making money in the industry to begin with.

I do this because of survival. I don't do this because I particularly like calling people out on their bullshit. I can't do your job, do mine, be underpaid, and then also have to walk around with years of PTSD. I can't do all of those things — something's got to give. So for me, one way of removing pressure and stress from the work that I'm doing is to talk about the reasons why there is pressure and stress. It's also not lost on me that the handful of Black photographers who have been doing this work for years did not necessarily matriculate into an industry where they could openly air grievances and not be severely punished for it.

I do this because of survival. I don't do this because I particularly like calling people out on their bullshit. I can't do your job, do mine, be underpaid, and then also have to walk around with years of PTSD. I can't do all of those things — something's got to give. So for me, one way of removing pressure and stress from the work that I'm doing is to talk about the reasons why there is pressure and stress. It's also not lost on me that the handful of Black photographers who have been doing this work for years did not necessarily matriculate into an industry where they could openly air grievances and not be severely punished for it.

So all these experiences — how do they connect to colonialism for you?

The pictures we think about when we think about the civil war — pictures that were manipulated to bolster the conspiracy theory of the lost cause — give you the backbone for American white supremacy, which is part and parcel with colonialism and imperialism. I think about the fact that the camera was used to help build illustrations of differences in humans for the junk science that is eugenics. I just don't know how anyone can pick up a camera and not think about the fact that the camera has been an exploitative tool.

People who say they “take pictures” are people who are highly suspicious to me, because I know you're not engaging in your practice in an ethical or moral way — you're taking versus collaborating with people. I just don't know how you look at the history over time and not see that colonialists and imperialism have weaponized the medium for white supremacy.

Gordon Parks brought humanity to his images. He made very specific decisions, which shows me how engaged he was both with the history of photography and the ways in which photography has been used. In the Atmosphere of Crime assignment, He chose to focus on the behavior of the policeman versus the “criminals” they were supposed to be capturing. the way he obscured faces, the way he protected the anonymity of the people that he was in collaboration with, and the nuance in which he also observed the policeman is startling. It's unlike anything you've ever seen in regards to crime photography.

This man gets no due for what he has done when it comes to the work that he's put behind a camera. We don't talk about Gordon Parks the way we talk about Henri Cartier-Bresson. We don't talk about James Van Der Zee the way we talk about fucking Annie Liebowitz. It’s the kind of aggravation I felt in college — constantly having the same white photographers shoved down my throat. I loved Bresson, but why the fuck did it take until I turned 30 to find out that Zora Neale Hurston was also a photo-ethnographer?