In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

Chris Gregory-Rivera:

Portfolio Overview

I remember the first time I met you — you came to visit WIRED — and how excited I was, because I had looked at your work for a long time, and I had no idea that you were Puerto Rican. Can you talk a bit about your background, where you grew up, what languages you grew up speaking?

I was actually born in New Mexico. My dad is half Puerto Rican, half Greek, and my mom is Puerto Rican. I've basically lived in Puerto Rico since I was four years old. We grew up in Puerto Rico — I spoke Spanish and English my whole life.

I left Puerto Rico when I was 18 to go to college. I got a scholarship and went to George Washington University in D.C. to study journalism. I was interested in writing at the time, so I decided I'm going to be a journalist — I started taking journalism classes, and it was horrible, mostly just because it felt very limiting. It’s just formulaic, uncreative, and so narrow in its scope. You can only have a certain amount of words, so then it feels incomplete — it feels disingenuous toward the thing you're trying to represent. In my mind, I was like, well, photography is a way of bridging that gap, creating a more complete picture. That was what attracted me to photojournalism.

I left Puerto Rico when I was 18 to go to college. I got a scholarship and went to George Washington University in D.C. to study journalism. I was interested in writing at the time, so I decided I'm going to be a journalist — I started taking journalism classes, and it was horrible, mostly just because it felt very limiting. It’s just formulaic, uncreative, and so narrow in its scope. You can only have a certain amount of words, so then it feels incomplete — it feels disingenuous toward the thing you're trying to represent. In my mind, I was like, well, photography is a way of bridging that gap, creating a more complete picture. That was what attracted me to photojournalism.

Do you recall seeing photography of your homeland or Puerto Ricans?

No — I met a lot of journalists, but by and large, photography wasn’t readily accessible other than the newspaper. There aren’t a lot of resources for photographers. And so, you had people like Jack Delano, who, whenever anybody was like “I want a photo book on Puerto Rico,” that's the book that you would buy. He's an FSA [Farm Security Administration] photographer similar to Dorothea Lange, and documented people who worked during the depression. That book really created what we think of as a representation of Puerto Rico, and it was done through a very particular aesthetic. Over the course of years, there haven’t been a lot of well-known Puerto Rican photographers able to put their point of view forward other than in the newspaper, the photojournalism space.

Something I've been thinking about is how so much of my identity has been formed by all these political forces. It's just this year when I started referring to myself as Afro Latina. It's been a wild process of discovering all that. I’m wondering how you've navigated your own identity? When I was first looking at your work, your name was listed as Chris Gregory. Now you’re listed as Chris Gregory-Rivera. I saw the shift and am wondering when that happened and how did it feel?

It was actually concrete the moment it happened. I think my identity is a little complicated because I'm very white-passing — not to mention, I have a perfect American accent. I speak like somebody from California — that's where my dad is — and so my vernacular English is really rooted in that experience. In some ways, I've been very fortunate and have had the privilege of being able to code-switch and have my appearance follow. Navigating the industry for me has been a little bit easier, on a basic surface level.

It was a perfect storm of things. I was sort of far away from the United States and I remember when I checked into the hotel, it was the first time a porter selected where I'm from, my nationality. There was an option for Puerto Rico, and I was like, “Shit, don't mind if I do!” I think there’s this perfect confluence of being abroad, being in a cohort of image-makers who are very committed to doing work about where they're from, in addition to also being very recognized editorially. I kind of had this soul searching.

I didn't consciously change my name when I moved to New York. The guy at the DMV was like, “I'm Puerto Rican. Trust me, I'm sorry for your mom, but you don't want to have both names on your license — it's gonna be a nightmare for paperwork.” And I’ve never thought about it, because nobody uses both last names here, but once I realized that, I went down this weird rabbit hole where I wanted to know why. I think a big part of it was that I didn't feel Puerto Rican enough in some ways, because of the way I look. There's plenty of Puerto Ricans who look the way I do in Puerto Rico, but it was just a mental thing. And I didn't feel American. But I resolved it by understanding that I was both — I realized that my name was the perfect way to illustrate that. For me, embracing that last name — Gregory-Rivera — gives me ownership over that and gives a better picture of who I am and my identities from a diverse heritage, if you will.

It was a perfect storm of things. I was sort of far away from the United States and I remember when I checked into the hotel, it was the first time a porter selected where I'm from, my nationality. There was an option for Puerto Rico, and I was like, “Shit, don't mind if I do!” I think there’s this perfect confluence of being abroad, being in a cohort of image-makers who are very committed to doing work about where they're from, in addition to also being very recognized editorially. I kind of had this soul searching.

I didn't consciously change my name when I moved to New York. The guy at the DMV was like, “I'm Puerto Rican. Trust me, I'm sorry for your mom, but you don't want to have both names on your license — it's gonna be a nightmare for paperwork.” And I’ve never thought about it, because nobody uses both last names here, but once I realized that, I went down this weird rabbit hole where I wanted to know why. I think a big part of it was that I didn't feel Puerto Rican enough in some ways, because of the way I look. There's plenty of Puerto Ricans who look the way I do in Puerto Rico, but it was just a mental thing. And I didn't feel American. But I resolved it by understanding that I was both — I realized that my name was the perfect way to illustrate that. For me, embracing that last name — Gregory-Rivera — gives me ownership over that and gives a better picture of who I am and my identities from a diverse heritage, if you will.

It’s powerful to hear that. Because I think it really is a journey of getting to that point of acknowledging both.

What is like to be assigned to publications that have staff who are not knowledgable about Puerto Rico?

I certainly felt a disconnect of perspective, especially as I started to cover Puerto Rico for larger outlets. There is a dynamic where you know a place very intimately, and editors or even journalists often don't have those same experiences. There are times where you have editors who are very open to that expertise and to your perspective. But then — especially when you're talking about a fast news cycle and newspaper work — there’s “this is the story, this is the perspective, go do it.” And I’ve felt that the assignment is way more complicated than that — I've lived in this place and returned to this place, I create work about this place and I can provide that context — but there's no space for that. These institutions are very fast, lean machines. Even if an editor is open, often there isn't the time to consider all of that context.

For me, I was always doing projects about Puerto Rico and people were very interested in them, but I think it was a hard sell. I think perhaps the institutions didn't quite know what to do with it because they didn't quite understand the historical and political context of Puerto Rico. That was an experience that I had over and over again until Hurricane Maria.

And then when Maria hit, I was commissioned by The New Yorker. I went down and I was really proud of the work I did because I knew the place. I was working with Jon Lee Anderson, who's an incredible writer on Latin America, speaks Spanish, and knows the history of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean very well. So it was this synergy of our unique conditions of having a team on the ground that really understood what we were doing.

The interest and the resources that have been put into covering Puerto Rico since Maria have been massive. So that suddenly created a lot of work and recognition, not only for me, but also for a lot of Puerto Rican photographers.

For me, I was always doing projects about Puerto Rico and people were very interested in them, but I think it was a hard sell. I think perhaps the institutions didn't quite know what to do with it because they didn't quite understand the historical and political context of Puerto Rico. That was an experience that I had over and over again until Hurricane Maria.

And then when Maria hit, I was commissioned by The New Yorker. I went down and I was really proud of the work I did because I knew the place. I was working with Jon Lee Anderson, who's an incredible writer on Latin America, speaks Spanish, and knows the history of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean very well. So it was this synergy of our unique conditions of having a team on the ground that really understood what we were doing.

The interest and the resources that have been put into covering Puerto Rico since Maria have been massive. So that suddenly created a lot of work and recognition, not only for me, but also for a lot of Puerto Rican photographers.

There's a colonial relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico. How does that relationship inform your work? Also, what do you think is important for people to know about the history of Puerto Rico?

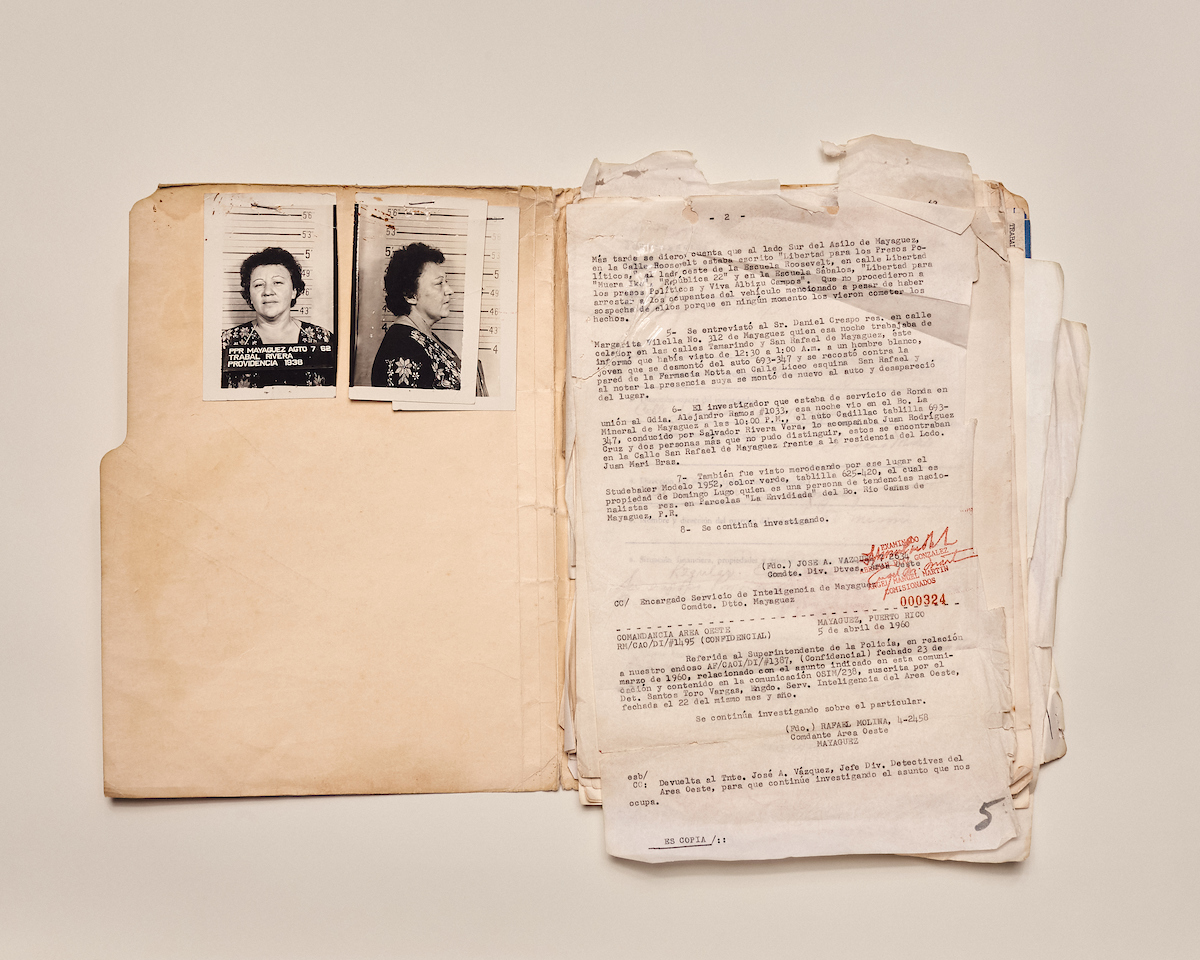

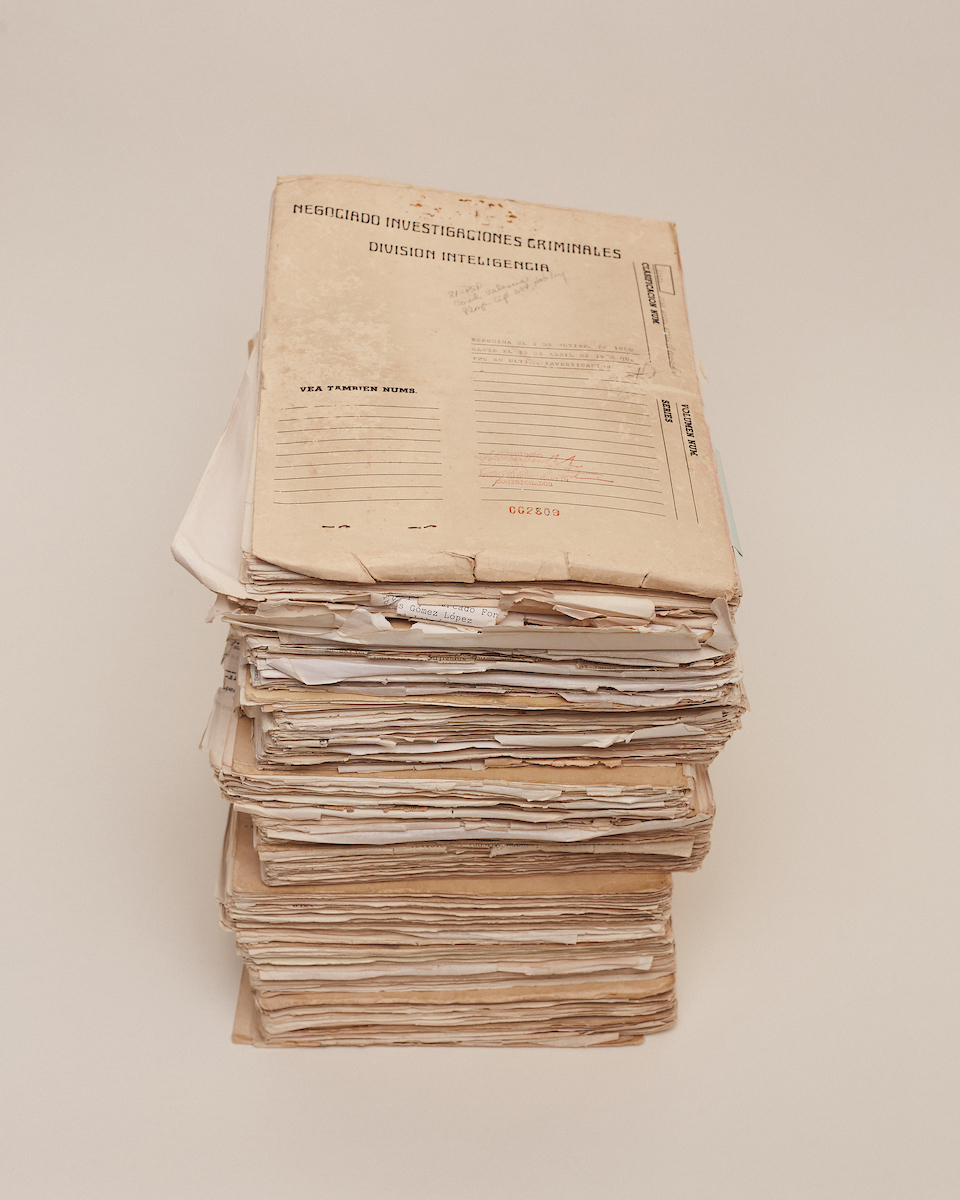

I mean, it's everything, right? The way that I photograph is completely informed by all of that. I'm really interested in this idea of memory and historic moments. My particular interest in that stems from being from a place where a lot of the history that's really shaped where we are today as a place, as a colony, has been suppressed and erased from popular understanding. Even from textbooks — a lot of textbooks in Puerto Rico stop in 1952. They're like, “And then we became the Commonwealth of the United States and we lived happily ever after.” Are you kidding me? It all began in 1952. Not to mention, the radical economic changes that happened in the 50s and 60s.

Once I became old enough and I started digging into this history, it was very eye-opening for me, because it answered questions about my identity and where I'm from. My family is originally from the mountains, and their political views, views on work and ethics, are completely informed by this period in time. My mom grew up in that time, she was afraid that she was being surveilled. So I always grew up with this idea, “oh, don't go to protests,” and I'd be careful because you're going to be followed. This literally transformed the psychological space in which people think about politics, autonomy, and self-determination.

The entire self-image Puerto Ricans have of themselves — their ability to self-determine and have open political discourse — was in a large part engineered by a foreign power. I'm interested in rescuing these moments in time and places to unravel a lot of that colonial trauma. I'm hopeful that, through understanding our history and our identity, we can have frank discourse around what it is that we want going forward and how we can heal. That's the hope — whether photography is able to do that, whether my work is able to do it, who knows, but that is the goal.

The industry is slowly changing and there are more prominent Latino and Latina photographers and editors, but it is still a white-dominated space. How do you balance being an ambassador of where you're from versus having the freedom to be more creative and explore?

If I can have a small conversation with an editor about the history of Puerto Rico and the context of things that we're covering — because I'm the only person that they're in contact with — that can do it for them. I feel like it's my responsibility. Is it tiresome to have to keep explaining a territory of the country that they are from? Yes, for sure.

I also take pride in it because I understand it as an opportunity to create more understanding about the place that I'm from. That's the particular context of Puerto Rico, too — there's this idea that they should know. Yes, they should know, but we're operating within a much larger institution and colonialism. According to the law, Puerto Ricans were “foreign to the United States in a domestic sense.” That is the legal definition for the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. If that's not clear, then I can't really expect people to understand. My duty is to educate, to use photography, and to use art as a tool for understanding and education to create a space in which we can move forward. Every photographer who does social justice or social work needs to understand and to educate everybody about what they're covering. That extends beyond my particular context as a Puerto Rican.