In conversation with Sara Urbaez

Edited for length and clarity

Edited for length and clarity

Chanell Stone:

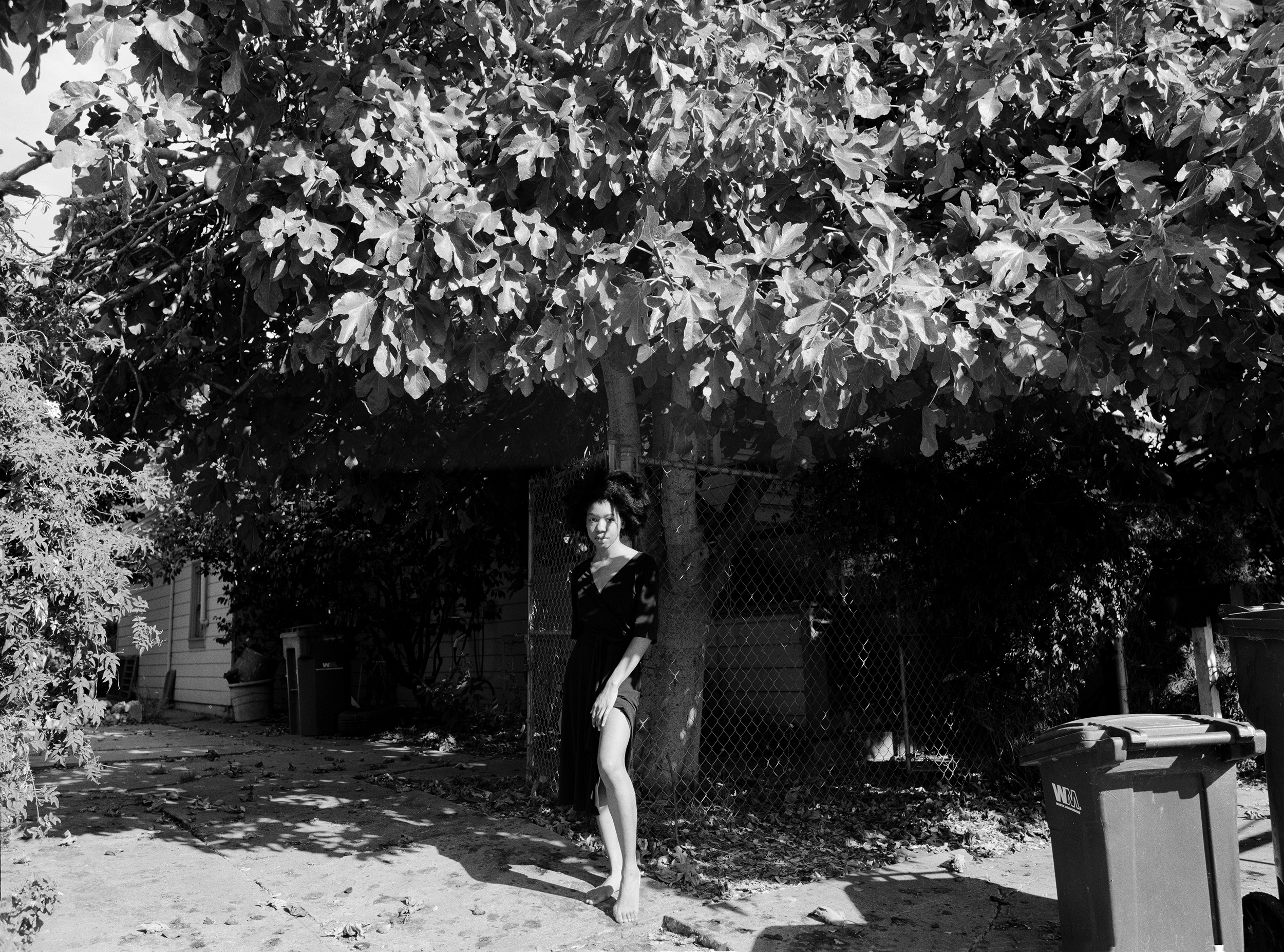

Natura Negra

Where did your inspiration come from to start doing self-portraiture in urban landscapes?

In New York City, I was attracted to all the plants and all the trees — everything was just so alive and there were a lot of vacant lots. So that's where my love for photographing urban nature started. Then I started to look at Oakland, and Oakland felt much greener than Los Angeles. I started looking at this history of urban nature and Black bodies, thinking about the connection between the two, because these are all major cities where there was a large Black population — like Brooklyn, for instance, Oakland, Los Angeles. And there's a lot of gentrification happening in all three of those cities, thus Black erasure is happening. The culture is getting lost in a sense or becomes a shell of its former self.

So I came back to Los Angeles to return home and photograph in my Grandma's backyard and look at my first memory of nature. What was that to me? And it was helping my grandma water plants. And she didn't have a lush field or like all these flower beds, but she had a space and she beautified it — that's where that interest came from.

So I came back to Los Angeles to return home and photograph in my Grandma's backyard and look at my first memory of nature. What was that to me? And it was helping my grandma water plants. And she didn't have a lush field or like all these flower beds, but she had a space and she beautified it — that's where that interest came from.

Can you talk about the importance of the series featuring only Black sitters?

I'm very interested in photographing Black people. That was something I deliberately focused on, because, I'm not seeing representation. I've grown up with all these images of white women, all the fashion magazines — that's the only reference point I had. And as I got older, I realized I've been brainwashed with all this imagery in a way that has subconsciously affected how I see myself and how Black people see themselves in general. I don't want to sound like I just pigeonholed myself, but it's the basis of my work. That's what I feel strongly about.

Your Natura Negra series spoke to me so deeply, because growing up in New York City, the nature you show is the kind of nature I grew up with. And it is so powerful to see a Black woman in that space and owning it. Your photographs make me think about how we overlook plants and landscape in an urban area. I had this narrative for a long time that I didn’t grow up in nature because it didn’t match the imagery of the white idealized version of nature I was bombarded with.

The media makes it seem like Black people just don't do nature. Like, we don't hike, we don't like water, we don't like bugs — we just live in cities and that's it. And I'm like, that's not true at all. And then learning about the history of photography, there's barely Black people as there is, but certainly not in nature. So who is nature for? You feel that when you go hiking, you don't really see that many Black people, but at the same time, that doesn't mean it's not for us.

I'm about dispelling all of these myths and democratizing nature in a sense — it’s for everyone. We all have history to this land, it's not just any one person. I wanted to highlight that in my work.

I'm about dispelling all of these myths and democratizing nature in a sense — it’s for everyone. We all have history to this land, it's not just any one person. I wanted to highlight that in my work.

Can you share your process with creating the photos?

I shoot alone usually because they're self-portraits. it's analog — I shoot on medium format film, it's not digital.

I love that, the depth of each imagery the tone.

Yeah, I feel it's more organic. It has like a realness to it, it's tangible. It's not translated into zeros and ones — it's a physical object. Now I'm looking at my family archive and mixing that into the project. I grew up in an urban inner city, but my grandparents are from the American south, like Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas. They grew up in rural, abundant nature, and moved here during the great migration to California to have a better life. I think a lot about what got lost in that migration — one of those things being our connection to nature. We were so adamant about leaving nature behind as a people because of all the trauma associated with it. I'd like to branch out and photograph in rural nature, going to the south.

What does it feel like to be like in front of the camera and to look through pictures of yourself in nature?

It feels like I'm mending relationships with my own personal self-image, because now I'm photographing me. It takes out the nervousness of someone else seeing me through the camera. It's me controlling my own narrative, how I look and where I am. It feels like I'm connecting to something innate. That's the best way I can describe it — being in those spaces around that nature, it just feels very right. It’s a sense of empowerment.